October 13, 2021

Automatic Identification Systems Essential to Maintaining Safe and Sustainable Fisheries

The U.S. is home to vibrant and diverse fisheries that provide a living for more than 1.7 million people and result in nearly $200 billion in revenue annually. From gumbo festivals to backyard clambakes, seafood is an integral part of American culture. However, these traditions and livelihoods are under threat from illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing. It’s estimated that a quarter of the world’s seafood sales are the result of IUU fishing, which can be anything from exceeding quotas to fishing out of season to plundering fish from another country’s waters. In 2019, the U.S. imported an estimated $2.4 billion in IUU-derived products. IUU fishing undermines honest U.S. fishers who follow the rules because it disrupts the seafood supply chain and drives down seafood prices through unsustainable fishing and forced labor.

To solve these problems, we must shine a light on IUU fishing, and Automatic Identification System (AIS) technology is a crucial tool in this fight. AIS devices allow ships to broadcast their location, identity, direction, and speed every few seconds. AIS was originally designed for safety — to help prevent crashes at sea — but has recently taken on a new role of transparency by allowing the public to monitor and track these ships, from where they fish to which ports they visit to which other ships they may meet up with. Read Oceana’s AIS Fact Sheet

Unfortunately, the U.S. only requires large boats (longer than 65 feet) — which comprise only 12.4% of the U.S.’s fishing fleet — to use AIS. Moreover, this small portion of ships is only required to have AIS turned on within 12 nautical miles of shore, an area that covers less than 8% of the country’s waters, and with no requirements while operating on the high seas. The U.S. cannot advocate for stronger international AIS requirements to combat IUU without following them first.

IUU fishing is a low-risk, high-reward activity, especially on the high seas where a fragmented legal framework and lack of effective enforcement allow it to thrive. To help fight IUU fishing and human rights abuses in the seafood industry, Reps. Jared Huffman (D-Calif.) and Garret Graves (R-La.) introduced the Illegal Fishing and Forced Labor Prevention Act. In September, a coalition of fishing interests sent a letter to Congress opposing a section of the bill that would expand the requirements for boats to broadcast AIS beyond U.S. national waters. The letter includes five points arguing against the proposed AIS improvements, which we respond to below.

1. “AIS is not superior to VMS for tracking fishing vessel activity.”

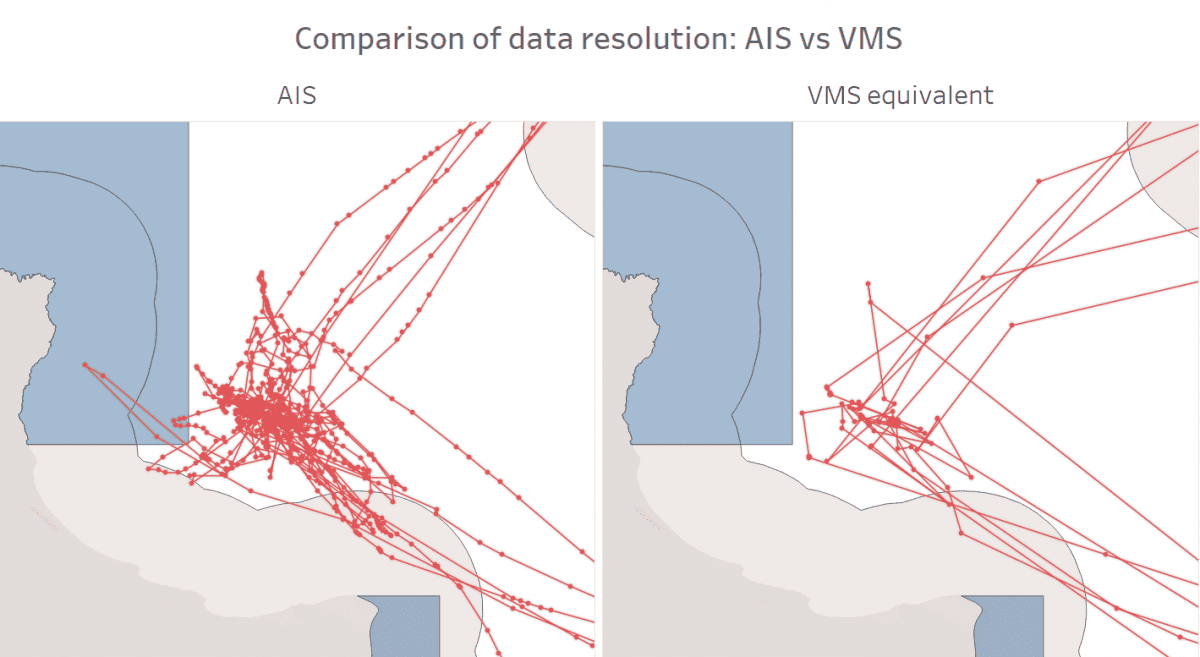

Vessel Monitoring System (VMS) technology is a satellite tracking system in which a ship sends its location directly to the government. While VMS has more reliable satellite coverage, it records a ship’s position as little as once per hour while an AIS device broadcasts its position every few seconds. A lot can happen in an hour and AIS fills in the gaps, helping ensure vessels are fishing safely and lawfully. This is especially important along the boundaries of areas where fishing is not allowed. Only knowing a ship’s location once per hour is not enough to tell that it has stayed out of “no fishing” zones.

AIS and VMS complement each other’s strengths and weaknesses and are best used in tandem. AIS can complete the picture of sparse VMS messages, and VMS can compensate for areas with poor satellite coverage.

Figure 1: The image on the left shows a fishing vessel’s movements within the Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary (white) and around the Channel Islands National Park (gray), where some fishing is allowed. Fishing is not allowed within the blue zones, which are state marine reserves. The image on the left shows the ship’s activity using AIS, while the image on the right shows what the same path would look like using only one ping per hour (the standard for VMS). With fewer pings, the full scope of the ship’s fishing activity is hidden, and its potential intrusion into a fishing-prohibited area is lost.

2. “AIS uses VHF radio signals that can be intercepted and spoofed.”

The fact that anyone can receive AIS signals is what makes the system so powerful in the fight for transparency. Organizations can collect these position messages and make them available so members of the public can use the data to improve safety and transparency. For example, an independent nonprofit called Global Fishing Watch (GFW), founded by Oceana in partnership with Google and SkyTruth, has brought together software engineers, marine scientists, and machine learning experts to develop an algorithm to identify when a vessel is fishing based on its movements in the AIS data. They used this algorithm to create a map so anyone can track fishing activity around the world.

While AIS signals can be falsified (aka “spoofed”), GFW has created an algorithm for identifying when this happens. According to GFW’s website:

“Our machine learning algorithms automatically separate signals coming from multiple vessels using the same [Maritime Mobile Service Identity (MMSI)] and also detect when the broadcast location is inconsistent with the location of the satellite that received the signal.”

There are numerous other organizations also working on analyzing AIS data, including exactEarth, Vulcan, MarineTraffic, OceanMind, Unseen Labs, and VesselFinder.

3. “VMS is based on secured end to end transmissions and used by federal govt (USCG, NOAA OLE) to track fishing vessels.”

The confidential nature of VMS undermines collaboration between the public and the government. In a recent American Security Project panel, former Air Force special agent in charge and current Navy Reserve division officer Charles Rego emphasized the value in collaboration between agencies and organizations in combatting IUU fishing:

“The NGOs, the private organizations, universities that have been looking at this problem set for decades at a time […] are the experts in this problem set. We learn from them. They’re the ones that kind of provide us a broader lens into what this problem typically looks like.”

VMS does not tell authorities when a vessel is fishing, but organizations such as GFW have developed sophisticated methods to do so, which would help the government with monitoring and enforcement. Even with VMS devices transmitting vessel activity, enforcement requires patrol boats and “eyes in the water” for 100% accuracy. With over 4 million square miles of ocean territory to cover, non-governmental organizations can aid the government’s task of patrolling U.S. waters.

Monitoring the seafood supply chain for IUU activity goes beyond fishing itself. Some fishing boats meet up with refrigerated cargo ships at sea to transfer their fish instead of coming into port. This behavior, known as “transshipment,” is a weak point in monitoring, as it disguises exactly who is catching what, potentially allowing illegally caught fish to be mixed in with the rest. VMS is used only to track fishing boats and therefore can’t detect transshipments, while AIS is required on all large boats and allows for a more complete picture of the actors involved in getting a fish from sea to shore.

4. “AIS coverage should not be extended to EEZ and high seas. AIS is open-source and can be seen by competitors.”

Oceana senior campaign manager Gib Brogan says:

“Our oceans are a shared public resource that should be managed for all. Widespread AIS requirements in the U.S. will provide far more benefits to support transparent fisheries management and enhance at-sea safety than any theoretical competitive disadvantage. The U.S. oceans have been fished so heavily for so long that there are unlikely any secrets that will be given up through transparency, and fisheries around the world have adopted robust transparency while remaining productive. The U.S. should follow suit.”

There are tremendous financial barriers that limit the number of ships even capable of fishing far offshore. In 2020, 2,341 vessels had visible fishing within 12 nautical miles of shore in the U.S., compared to just 232 that fished on the high seas. Fishing within the 12 nautical mile zone accounted for 36% of all fishing in U.S. waters, even though it accounts for just 8% of the area. AIS requirements already apply in the area where potential competition is heaviest. Further, AIS only shows where a ship has been, not where it is going or where the fish are.

5. “AIS’ main function should remain for vessel safety and be required to be on only when within 12 nautical miles from shore.”

AIS has many benefits beyond vessel safety. Its importance as a safety tool away from shore should not be underestimated. Commercial fishing is the deadliest job in the U.S., with an on-the-job fatality rate over 40 times the national average. Ship crashes and other accidents can happen anywhere and do not stop at the 12 nautical mile line; neither should AIS. In August of this year, a man was killed in a boat crash 60 miles offshore, and another was injured. AIS helps to prevent these incidents from occurring and allows for faster response times when they do.

IUU fishing operates in darkness, enabled by an ocean that is difficult to oversee and a patchwork of laws that only cover part of the supply chain. Expanding AIS will give the United States a stronger position in advocating for transparency globally, improve the safety of U.S. waters, and allow for more sustainable and efficient fisheries monitoring. To learn more about Oceana’s campaign to stop illegal fishing and increase transparency at sea, please click here.

Take Action Today: Call on President Biden to expand transparency at sea and traceability in the seafood sector. CLICK HERE

MOST RECENT

August 22, 2025

Corals, Community, and Celebration: Oceana Goes to Salmonfest!