March 23, 2017

Behind the Scenes of Marine Mammal Rescue

On a misty afternoon last October, I visited The Marine Mammal Center in Sausalito, California—just north of the Golden Gate Bridge. Situated atop a hill overlooking picturesque open green fields that meet the ocean, the Center has been dedicated to rehabilitating sea lions, harbor seals, fur seals, and elephant seals since the 1970’s. Scientifically speaking, all of these marine mammals are in the order Pinnipedia and are consequently referred to as pinnipeds.

View of the Pacific Ocean from the front of The Marine Mammal Center.

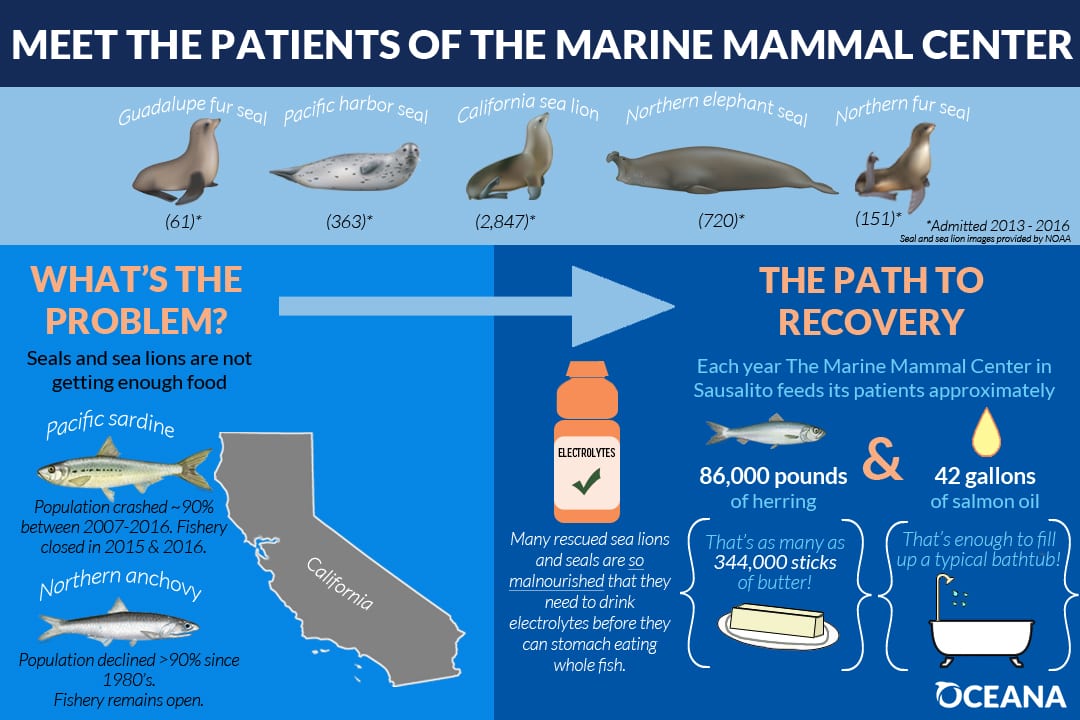

California sea lions in particular had been hard hit in recent years, stranding on beaches up and down the state in unprecedented numbers. The Center became inundated with unhealthy animals in historic numbers over the last four consecutive years. This crisis led the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to declare an Unusual Mortality Event— defined as unexpected strandings of animals that die in large numbers that necessitates an immediate response—spanning 2013-2016. News outlets highlighted the sea lions’ plight, particularly in 2015 when more than 3,000 California sea lions stranded state-wide. The Sausalito location of the Marine Mammal Center took in 1,372 of these stranded animals that year, an all-time high for this location, which takes in animals from 600 miles of coastline from San Luis Obispo County north to Mendocino County. As news coverage of the crisis began to shift last year, I wondered how some of the coast’s most iconic marine mammals were doing and what their outlook is for 2017.

To address my mounting curiosity, Dr. Jeff Boehm, Executive Director of The Marine Mammal Center, generously provided a behind the scenes tour. Embarking on the tour from the lobby, a digital board listed the current patients—all youngsters.

Current patients admitted for rehabilitation during my visit to The Marine Mammal Center.

Dr. Jeff Boehm and Ashley Blacow discuss how pinniped rehabilitation has evolved over time to provide state-of-the-art care to marine mammals in need.

Harbor seals and elephant seals typically come to the Center as babies, but sea lions often come in as yearlings (1-2 years old), as young sea lions spend more time with their moms after birth. Recently, sea lions have been separating from their moms even younger, when they are pups of only four to seven months in age, a time when they should still be receiving mom’s milk. The day I visited the Center, only four patients were in for treatment compared to 250 at this time in 2015. In some weeks during 2015, twelve new patients were admitted per day! Every pinniped checked into the Center is provided with a unique identifying name—like Valentino, Grey Louie, and Chompers. The animals’ names are decided by staff and members of the public who report the stranded animals. Once admitted to the Center, an animal is examined by a specially trained veterinarian who performs an exam to determine what caused the animal to strand.

Why So Many Strandings?

California sea lion pup Fat Tues, who was rescued on Mardi Gras last year, was one of more than 200 seals and sea lions in The Marine Mammal Center’s care at this time last year.

The stranding crisis over the last several years is due to insufficient amounts of energy-rich forage fish like sardines and anchovy. These small food fish pack a punch of nutrients like omega 3-fatty acids to sea lions and seals—these are the same heart healthy benefits people receive from eating these fish. When forage fish are in short supply, sea lion moms are unable to provide enough milk to their pups and these pups are too young to search for food on their own. The result is that the mothers abandon their pups, or if mom had been gone too long the starved pups try to search for food on their own. In the end, sea lion pups become dehydrated and malnourished. The compromised health of these mammals leaves them susceptible to secondary infections and organ failure, such as compromised liver and gastrointestinal tract functions. Many sea lion moms have not even been able to carry their pups to full term, and for the ones that do, many of their pups are underweight. For example, most California sea lion pups born near the Channel Islands in June weigh 13-20 pounds. At six to nine months they should weigh 50-70 pounds, but in 2016 were just half of that—only 20-29 pounds. Last year, pup weights were the lowest ever documented by NOAA researchers—31 percent below normal and the lowest ever seen in 41 years since monitoring began at the Channel Islands—and the number of pup births was down from 2015.

Veterinary experts perform an admit exam on a California sea lion at The Marine Mammal Center in Sausalito, California.

In recent years, populations of Pacific sardine and Northern anchovy have crashed to the lowest levels in decades. According to the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) 2016 sardine assessment, the Pacific sardine population took a nosedive and dropped by roughly 90 percent between 2007 and 2016. During the crash, continued fishing on the population made the situation even worse. In response to this collapse, federal fishery managers closed the directed commercial fishery in 2015 and in 2016. [You can read more about the role of fishing in the sardine collapse here]. Unfortunately, anchovy have simultaneously plummeted to historically low levels. Federal scientists recently presented data showing the anchovy population declined more than 90 percent since the 1980’s. Yet, in October 2016, NMFS set an annual catch limit for the central subpopulation (off California) of northern anchovy at 25,000 metric tons, which may actually exceed the entire remaining anchovy population. It is essential that fishery managers consider the dietary needs of predators and include a safety net to ensure that fish populations can replenish themselves in times of unfavorable ocean conditions that can cause severe declines. If fish are not given a reprieve during such times, continued fishing pressure exacerbates the magnitude of the decline and prevents these critical food fish from recovering.

What is Rehabilitation?

As Dr. Boehm explains, it’s not as simple as feeding the pups fish for a few days and releasing them back out into the ocean. Many of the pups are so unhealthy that their livers cannot process the fats in whole fish. In fact, their nutritional recovery is quite similar to humans when we suffer from the flu. After being sick, and unable to eat for several days, we have to work our way back up to larger meals, perhaps starting with crackers, toast, or soup broth. In many cases, sea lion pups are in need of a boost in electrolytes and are fed an equivalent to Ensure or Gatorade. The Center uses a hydrating formula called Emeraid, a powder containing amino acids, protein, and vitamins that is mixed with water to rehydrate the patients. Once electrolyte levels are normal, the pups are upgraded to “fish smoothies” (ground up fish) which are administered via a feeding tube. Once the patients can process the fish smoothies, whole fish are introduced. Herring is the preferred, most efficient source of nutrients to feed mammals at the Center; however, they also use smelt, mackerel, and squid. Squid is not as high in calories, but is a good source of water since sea lions obtain water through the food they eat. Each year the Center feeds approximately 86,000 pounds of herring and 42 gallons of salmon oil to its patients.

Volunteer Kathy Blackwell tosses a bucket of fish to a pool of California sea lions rehabilitating at The Marine Mammal Center in Sausalito, California.

Between 2014 and 2016, the Center rehabilitated and released back into the wild 1,534 pinnipeds of which 827 were California sea lions.

The Center has developed this strategic system of recovery over time. Coupled with a fish kitchen and surgery suite, the Center also serves as a teaching hospital and a research facility. Satellite tracking of released animals and necropsies (autopsies for animals) of all animals that do not survive allows the Center to learn more about each individual’s condition, and that provides insight into ocean changes.

What’s the Prognosis for 2017?

We remain hopeful that California’s forage fish will recover and provide more food to sea lions and other predators, like whales and dolphins. However, with likely a third consecutive commercial sardine closure on the horizon, as it does not appear these forage fish have rebounded, and with no clear evidence of anchovy recovery, the outlook is not bright. Only time will tell how many sea lions and seals will strand this year. Rest assured that The Marine Mammal Center is well prepared to nurse as many of them back to health as possible. In the long-term we must ensure that fishery management accounts for the dietary needs of predators and reduces fishing pressure when fish populations decline. Successful forage fish management must also include a safeguard in catch level calculations that takes into account how short and long-term changes in ocean chemistry (El Niño, climate change, etc.) will affect fish populations—and in turn the larger animals that depend on forage fish for food.

How Can You Help?

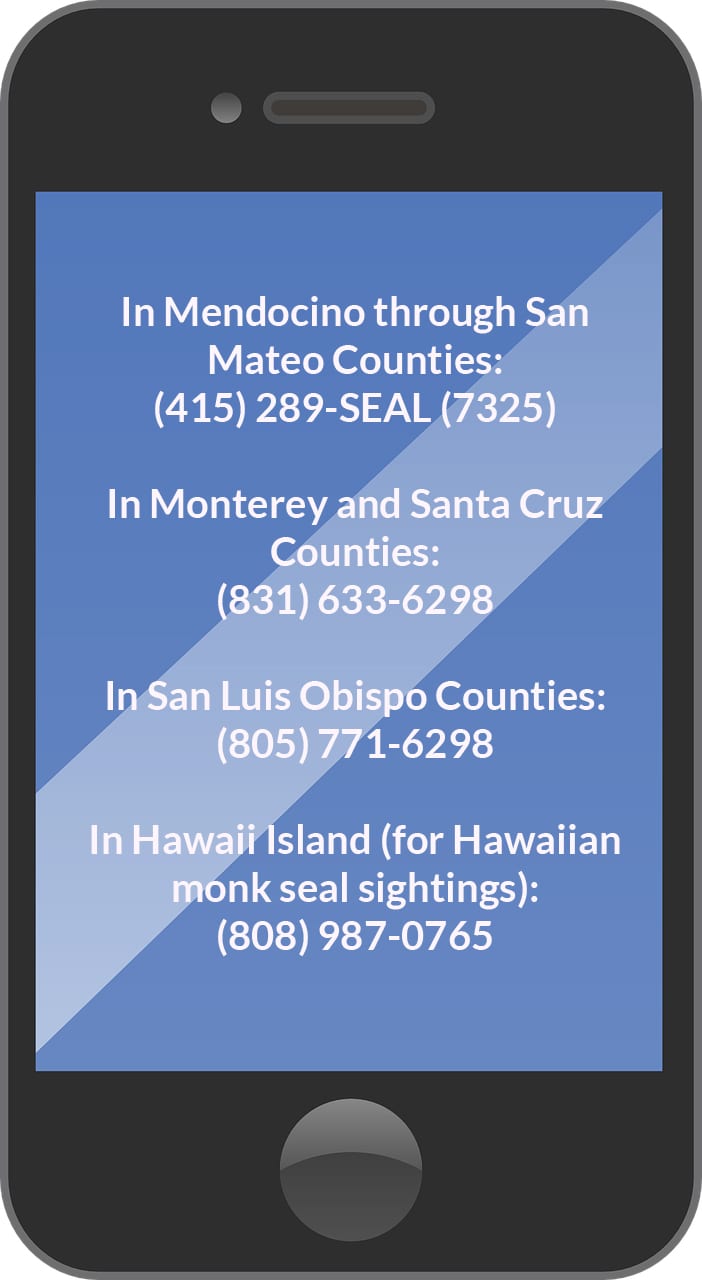

- If you think a marine animal needs attention, do not approach or disturb it. Instead, call The Marine Mammal Center with as much information as you have. Trained staff will assess the situation and if necessary will rescue the animal and safely transport it to the nearest available rehabilitation center. (If you are outside of California or Hawaii, call your closest marine mammal rescue center).

- Click here to learn more about how you can support Oceana’s efforts to improve management of forage fisheries to ensure enough fish are left in the ocean to feed dependent predators.

MOST RECENT

September 3, 2025

Air Raid Panic to Informed Skies and Seas: The National Weather Service in a Nutshell

August 29, 2025

August 22, 2025

Corals, Community, and Celebration: Oceana Goes to Salmonfest!