May 26, 2017

Shark Fact Friday #4: Fossil Friday Edition

Welcome to Shark Fact Friday, a (mostly) weekly blog post all about unique sharks and what makes them so awesome.

This week will be about a prehistoric relative of modern-day sharks called Helicoprion. “Heli” means spiral and “prion” means saw in Greek. An appropriate name considering that Helicoprion fossils look like this:

Before we get to what in the world that fossil is showing, a little background: Helicoprion was swimming the Earth’s seas about 290 million years ago. They are long extinct now, so scientists have had to piece together information about Helicoprion from fossils. This can be challenging for sharks and their prehistoric relatives because they tend to not fossilize well. Fossils form when an animal dies and gets buried in mud or silt. The soft parts of the animal usually decompose away, leaving the hard parts, like the skeleton, to form a fossil and harden into rock. However, shark skeletons are made from cartilage instead of bone, so the only hard parts that tend to fossilize are the teeth. Occasionally some skeletal cartilage will fossilize, but the teeth are far more reliable.

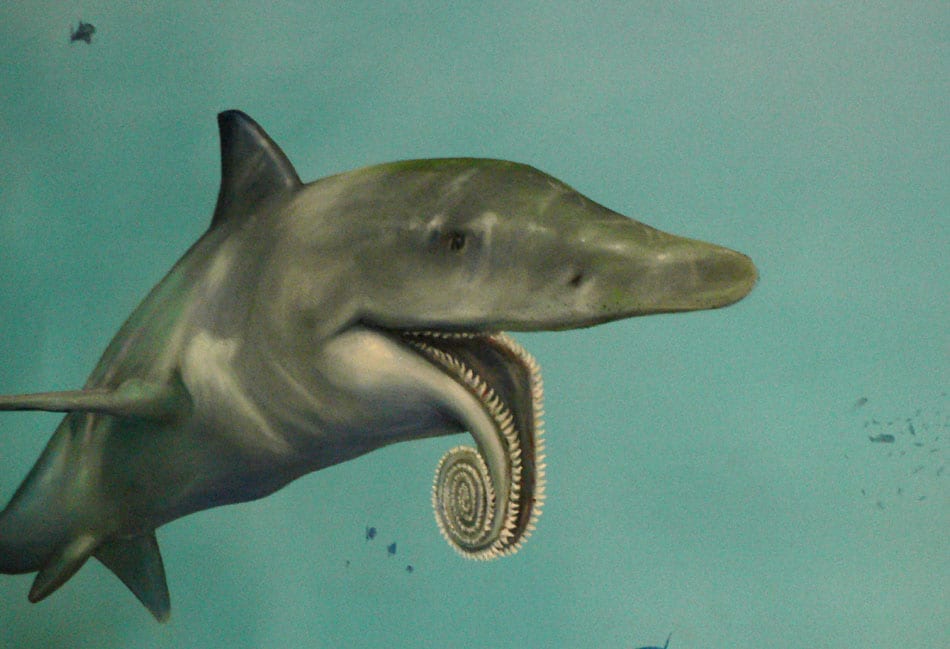

So that left scientists with these crazy swirls of teeth known as tooth whorls and not much else, leaving a lot of questions such as: Where were the these whorls located? Did they hang on the outside of the jaw like this?

On the inside of the jaw like this?

Or was it located somewhere else on the body entirely? And what was it used for?

A 2015 paper looked to answer that exact question. A fossil that contained intact jaws showed that the tooth whorl occupied the entire length of the Meckel’s cartilage, the main component of the lower jaw. So the buzzsaw set of teeth was surrounded by the shark’s lower jaw, inside the mouth.

The authors also found that, despite how fearsome the teeth look, Helicoprion species likely fed on soft-bodied prey like the prehistoric relatives of octopus and squid. They believe that the front teeth hooked and dragged prey into the mouth, the middle teeth did the cutting, and the ones near the back cut and pushed prey deeper into the mouth to be swallowed. That would make the strange tooth arrangement function more like a multi-use tool rather than a buzzsaw!

There are a lot of things we don’t yet know about the ancient oceans, but thanks to the discoveries of new and increasingly intact fossils, scientists can come to conclusions about what these animals might have looked like, how fossilized parts functioned, and even what they ate.