November 2, 2015

To Every Scam There Is a Season: Report Reveals Salmon Fraud Prevalent in Winter

It’s January. Snow is falling and you decide it’s a good night to take your sweetie to that nice seafood place that just opened down the street. The special is wild Pacific salmon fillet, served with caper butter, a farro crostini and a single dry-aged Brussels sprout. It pairs quite well with the chardonnay, says the waiter. The lighting is perfect. The muted conversation of your fellow diners blends subtly with a tasteful Americana tune and the clink of dinnerware. The chardonnay sounds nice, but maybe instead you’ll go with a GLASS OF LIES AND A SIDE OF TRICKERY! *dramatically overturns table*

Because according to the a report out today from Oceana, there’s a good chance that’s what you’ll get if you order wild salmon at a restaurant during winter months.

Salmon Mislabeling

In 2013 Oceana released a report on its DNA analysis of more than 1,200 seafood samples collected across the country. Fraud was widespread (33 percent of the samples tested were mislabeled), but salmon had a lower rate of mislabeling, at 7 percent. The investigators reasoned that the low rate of mislabeling may have been due to most of the samples being collected in grocery stores during summer months when fresh wild salmon is readily available in the market.

Last year Oceana researchers collected 82 samples of salmon from restaurants and grocery stores in several cities during winter months when wild salmon are less likely to be available. Overall, they found close to half of the samples were mislabeled (43 percent), and rates of mislabeling were especially higher in restaurants vs. grocery stores (67 percent, vs. 20 percent). The most common form of mislabeling was farmed Atlantic salmon being represented as” wild” salmon. These trends persisted when comparing all of their salmon data (466 samples) spanning over four years.

So what’s the big deal? Marketers fluff up the names of food all the time to make it sound fancier, fresher, or more exotic. Diners are still getting their salmon, albeit with its name tweaked a bit for effect. Salmon is salmon, right?

Salmon is not just Salmon

Salmon is the most consumed fish in the U.S., surpassing our former favorite, tuna, in per capita consumption in 2013. America has some of the best-managed fisheries in the world. Every domestic wild-caught salmon receives a “best choice” or “good alternative” rating from Monterey Bay Aquarium’s Seafood Watch sustainability guide. Some of the Pacific salmon species caught in U.S. fisheries like Chinook and sockeye are highly-valued fish, preferred by chefs and consumers for their taste and nutritional profiles. These fish come from well-managed populations, and the timing and methods by which they are caught cause minimal impact to the oceans.

Salmon is the most consumed fish in the U.S., surpassing our former favorite, tuna, in per capita consumption in 2013. America has some of the best-managed fisheries in the world. Every domestic wild-caught salmon receives a “best choice” or “good alternative” rating from Monterey Bay Aquarium’s Seafood Watch sustainability guide. Some of the Pacific salmon species caught in U.S. fisheries like Chinook and sockeye are highly-valued fish, preferred by chefs and consumers for their taste and nutritional profiles. These fish come from well-managed populations, and the timing and methods by which they are caught cause minimal impact to the oceans.

While a variety of species are caught wild in the Pacific Ocean, Atlantic salmon is a unique species that is commercially extinct in the wild in U.S. waters, but today is the type of salmon most commonly farmed throughout the world. This makes up the majority of the farmed fish we import. In other words, in the U.S., if it’s Atlantic salmon, it’s most likely farmed, and if it’s farmed, it’s most likely Atlantic salmon.

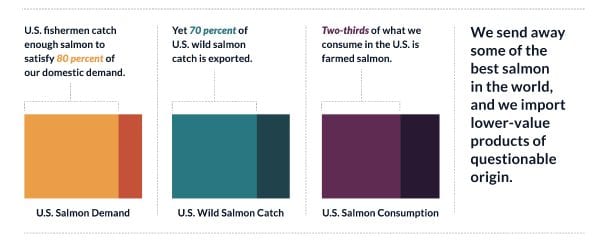

The valuable Pacific species caught in U.S. waters would be enough to satisfy 80 percent of our current demand, yet 70 percent of that is exported to be processed. Once our salmon enters the global seafood supply chain it’s anyone’s guess what happens to it. Oceana’s analysis of trade data indicates that of the 85,000 metric tons of wild salmon exported to China in 2013, only an estimated 37,000 metric tons returned to the U.S. In other words, according to Oceana’s report, we send away some of the best salmon in the world, and most of what we get back is lower-value products of unknown origin. Two-thirds of the salmon that Americans consume is farmed, and salmon farms can be bad news for the oceans.

Down on the Farms

Margot Stiles, Director of Science and Strategy at Oceana has seen these farms. She worked on a campaign to protect Chile’s pristine Tortel region from the expansion of large-scale salmon farming into the area’s waters.

“The net pens look clean on the surface, but when you take a camera underwater it’s all murky with salmon poop and bacterial mats growing in polluted water,” Stiles said. “Every time there’s a storm, that dirty water spills into surrounding areas along with uneaten pellets of feed and antibiotics. In Chile, salmon are an invasive species. When they escape they can outcompete or just plain eat the native fish that are an important part of the ecosystem. There are some salmon companies making improvements, but without traceability the odds are you’re going to get a lower-quality product.”

In addition, according to Oceana’s report, despite some improvements in the amount of feed needed to produce the final product, farming continues to put pressure on populations of forage fish that are used to feed the carnivorous salmon.

Up by the Bay

That imported salmon makes up most of what we eat in the U.S. baffles people like Verner Wilson III, for whom wild salmon holds both economic and cultural significance. Wilson, a recent graduate of Yale University’s School of Forestry and Environmental Sciences, is three-quarters Yup’ik Eskimo—an indigenous people who have been fishing Alaska’s Bristol Bay for thousands of years. In the 1930s, Wilson’s grandfather, a Finnish salmon fisherman, immigrated to Alaska after hearing about Bristol Bay’s legendary salmon runs.

[[{“fid”:”85559″,”view_mode”:”full”,”fields”:{“format”:”full”,”field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]”:””,”field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]”:””,”field_blog_image_caption[und][0][value]”:”Wilson, brother, and father fishing on Bristol Bay”,”field_blog_image_credit[und][0][value]”:”Verner Wilson III”},”type”:”media”,”attributes”:{“height”:360,”width”:480,”class”:”media-element file-full”}}]]

“Following my grandpa’s footsteps, my dad started fishing at a young age–as I did with my father,” Wilson said. They depended on salmon not just for their cash income, but also to put food on the table. Until the 90s, Wilson told me, the people of Bristol Bay were able to depend entirely on the salmon harvest until cheaper Norwegian and Chilean farmed salmon flooded the market. The prices of wild salmon crashed.

Since then Alaskan fishermen have put considerable effort into distinguishing their products from farmed imports through Regional Seafood Development Associations, which market their salmon with the help of regional taxes. Christa Hoover, executive director of the Copper River/Prince William Sound Marketing Association told me that the RSDAs like hers are vital for individual salmon fishermen to be able to compete with large-scale farming operations. Despite the benefits Alaskan fishermen enjoy from this promotion, they still face numerous challenges.

“Salmon fishing is a gamble,” Wilson told me. “You never know how big the run is going to be that year, what the weather will do, or if you’ll have engine trouble out on the water. It can be a really dangerous job. We put up with it because we love it. We know that we’re providing a wild, natural, sustainable product that’s healthy for people. That’s why it’s damn frustrating to hear that people are lying and cheating to pass off their products as one of ours. They’re basically riding on the backs of our hard work and risk” he said.

Solutions in Traceability

So no, salmon is not just salmon. Our choices matter—to the livelihood of American fishing communities, to our economy, and to the health of the oceans. A diner feasting on a wild-caught Alaskan king salmon should be able to rest in the knowledge that she is enjoying a healthy fish from a healthy population in healthy, well-cared for waters. She might be willing to pay extra for that knowledge. But that value the diner perceives requires a well-regulated and transparent seafood supply chain. And that’s something we just don’t yet have.

The Obama administration is poised to enact rules that would prevent Illegally caught and fraudulent fish from entering U.S. markets. The administration has indicated that it plans to phase in these measures by requiring traceability for a few species that are “at risk” of illegal fishing and fraud. That information would only follow the fish to the first point of entry into U.S. commerce. However, recent cases demonstrate that seafood fraud does occur after products have entered the U.S., and throughout the supply chain. It is not clear that salmon will be among those initial “high risk” fish for which the task force will enact traceability requirements.

[[{“fid”:”85560″,”view_mode”:”full”,”fields”:{“format”:”full”,”field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]”:””,”field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]”:””,”field_blog_image_caption[und][0][value]”:””,”field_blog_image_credit[und][0][value]”:”Pixabay”},”type”:”media”,”attributes”:{“height”:233,”width”:400,”class”:”media-element file-full”}}]]

“Our study showed that fish with a story were less likely to be mislabeled than those that were sold with more vague labels,” said Beth Lowell, senior campaign director at Oceana. “Information about what the actual fish is, whether it is farmed or wild, and where and how it was caught, allows consumers to make more informed decisions about their seafood. The Obama administration should require documentation for all seafood to verify that it was legally caught, and also mandate traceability throughout the entire seafood supply chain, to protect seafood buyers, honest fishermen, seafood business and our oceans,” she said.

Until that happens, dear salmon eaters, remember:

If it’s winter, and the menu offers “wild,” “Pacific,” or “Alaskan” salmon, ask for more information, like the specific species. If the restaurant can’t provide that information, order something else, unless you’re okay with possibly eating mislabeled farmed salmon. For more details, and more tips about getting responsibly-sourced salmon, visit oceana.org/salmonfraud.

Happy eating.

This post originally appered on Scientific American Food Matters on October 28, 2015

MOST RECENT

August 29, 2025

August 22, 2025

Corals, Community, and Celebration: Oceana Goes to Salmonfest!