February 23, 2022

Are U.S. Sharks in Trouble?

“Managing fisheries is hard: it’s like managing a forest, in which the trees are invisible and keep moving around.” – John Shepherd

Fisheries management can be incredibly nuanced and difficult to understand, but the key underlying principle is to ensure that fish populations, or stocks, do not decline to a level where they can no longer recover or rebuild. In order to determine whether a fish stock is being managed well, we need to know two key facts:

- Is overfishing occurring: is the population caught at a faster rate than it can reproduce?

- Is it overfished: is the population size too small?

Once these two questions have been answered, fisheries managers can start to set catch limits, allocate quota between different fisheries, establish time or area closures if necessary, or, in the worst cases, entirely shut down a fishery. When a stock is managed well, theoretically, we should be able to fish forever, with populations continuing to replenish themselves. However, without proper management, when too many fish are removed, the fishery will continue to decline to the point of extinction.

Thanks to the main federal fisheries law, the Magnuson-Stevens Act, and its conservation requirements, the U.S. has rebuilt over 45 fisheries to sustainable levels.

Since all fish species have different lifespans and reproductive behaviors, there is no one-size-fits-all method to determine whether a fishery is sustainable. For example, some fish species can spawn hundreds or thousands of eggs at one time and mature quickly, which makes it easy for those fish to replenish their populations. But some species, including many shark species, live for a long time, mature late in life, and have relatively few young. All of this creates a perfect recipe for overfishing, and a situation that poses challenges for sustainable management.

Many scientists have acknowledged that not only do shark fisheries need to be very carefully managed to achieve sustainability, but that there are also few real-world examples of sustainable shark fishing. In fact, globally, only about 9 percent of all sharks caught are considered biologically sustainable, although those fisheries aren’t necessarily managed well.

So how well is the United States managing its shark stocks?

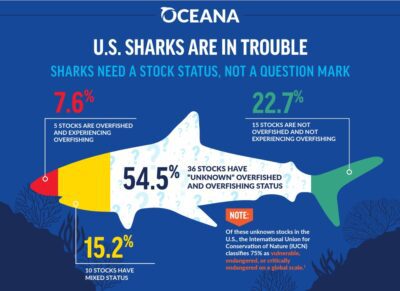

The federal government releases a kind of “report card” once a year, with quarterly updates, that gives an overview of how the 460 stocks or stock complexes (groups of stocks) in the United States are being managed, including whether they are experiencing overfishing or are overfished. The latest government report lists 66 shark stocks in U.S. waters. This includes sharks that are the target catch of a fishery, those that are not targeted and “prohibited species” – species that are not allowed to be caught, but many of which are still incidentally captured in fishing gear. Of the 66 shark stocks, over half have “unknown” overfishing and overfished statuses, meaning that fisheries managers lack the basic information needed to create proper, stock specific fisheries management actions.

These numbers illustrate the problem:

This dearth of information for most of our shark stocks hampers good management for these vulnerable species. Even species that are not targeted in fisheries could be accidentally captured at such high numbers that their populations are declining without fisheries managers even knowing. While the Magnuson-Stevens Act has made the U.S. a global leader in fisheries management, when it comes to sharks, we still have a lot of work to do.

To learn more about the status of U.S. shark stocks, see Oceana’s full infographic here.

MOST RECENT

September 3, 2025

Air Raid Panic to Informed Skies and Seas: The National Weather Service in a Nutshell

August 29, 2025

August 22, 2025

Corals, Community, and Celebration: Oceana Goes to Salmonfest!