June 5, 2025

Blurred Lines: China and Korea Compete for Shared Fisheries

Fish don’t recognize political boundaries and often migrate freely between national waters, making international cooperation essential for sustainable management. A clear example of this challenge is unfolding between China and South Korea, two close maritime neighbors separated by the resource-rich Yellow Sea. This shared body of water has long been a hotspot for conflict, as both countries have overlapping claims and conflicting interpretations of jurisdiction. For decades, disputes over maritime boundaries, fishing rights, and access to resources have complicated enforcement efforts and contributed to overfishing in the region.

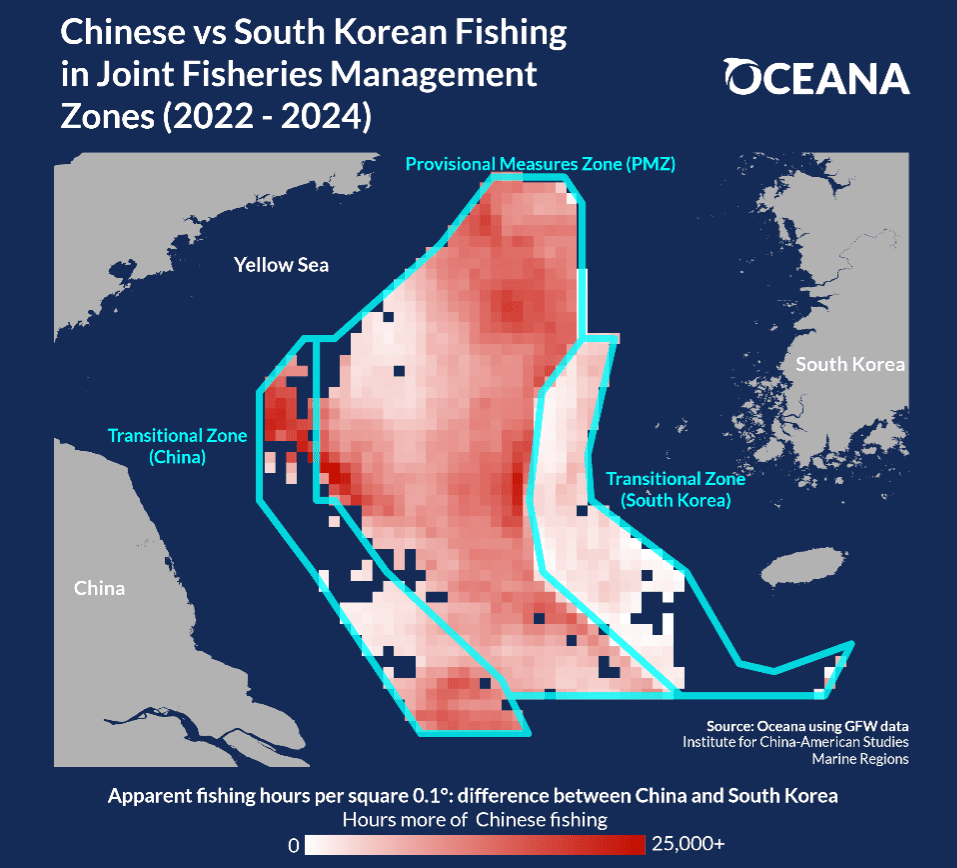

In 2001, the two countries signed a bilateral fisheries agreement establishing a co-managed area called the Provisional Measures Zone (PMZ) within the contested area, where both countries have fishing rights. Within this zone, both Chinese and South Korean vessels are permitted to fish. Surrounding the PMZ, there are “transitional zones” designated for each country, with an agreement to gradually reduce fishing in each other’s transitional zones and eventually return control of these zones back to their respective country. However, since these zones were established, Chinese fishing vessels and the Korean Coast Guard have frequently clashed – at times violently – over Chinese incursions into South Korean territory. South Korean fishers have also complained that Chinese fishing dominates the PMZ area. Negotiations over these waters are ongoing, with the two countries signing recent agreements in 2022 and 2023 to reduce fishing in each other’s territories.

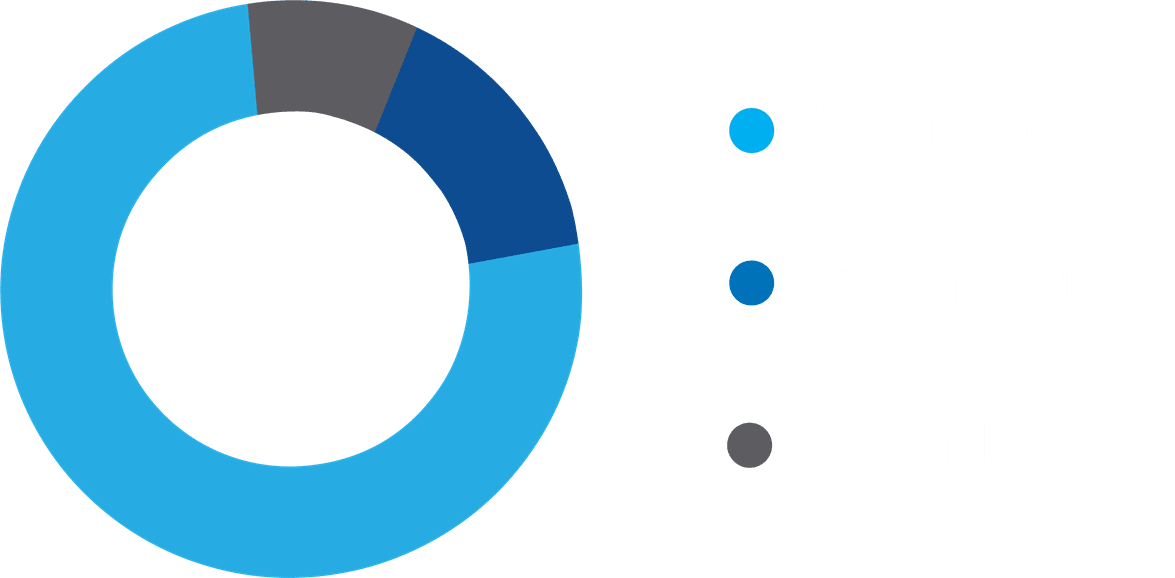

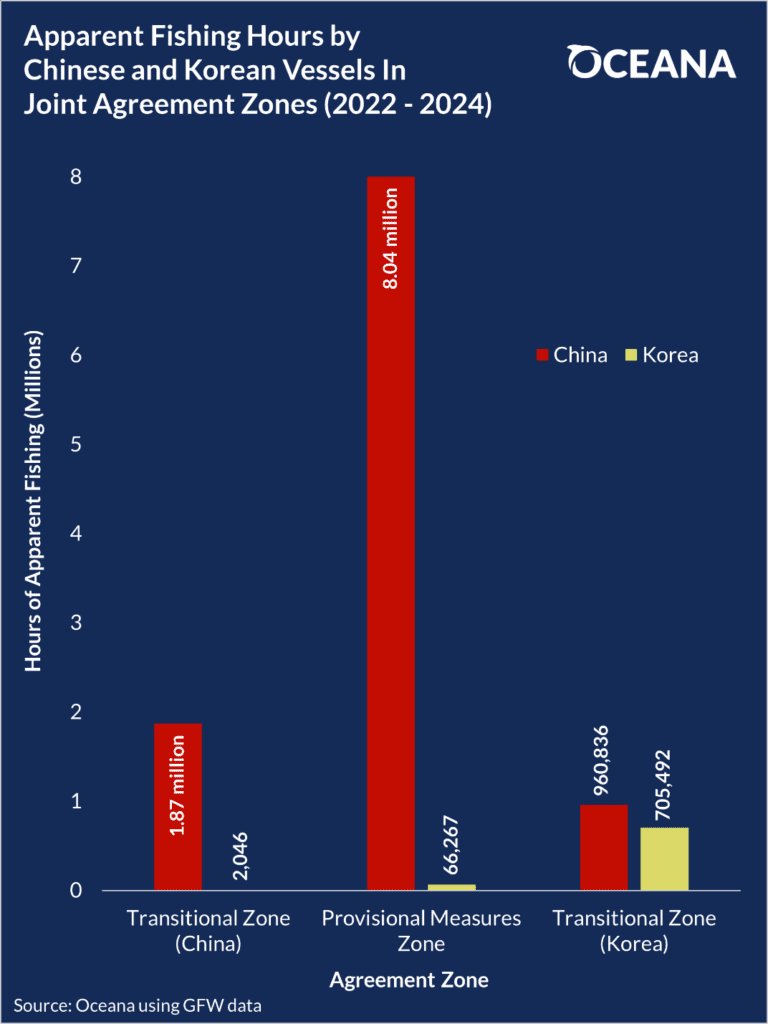

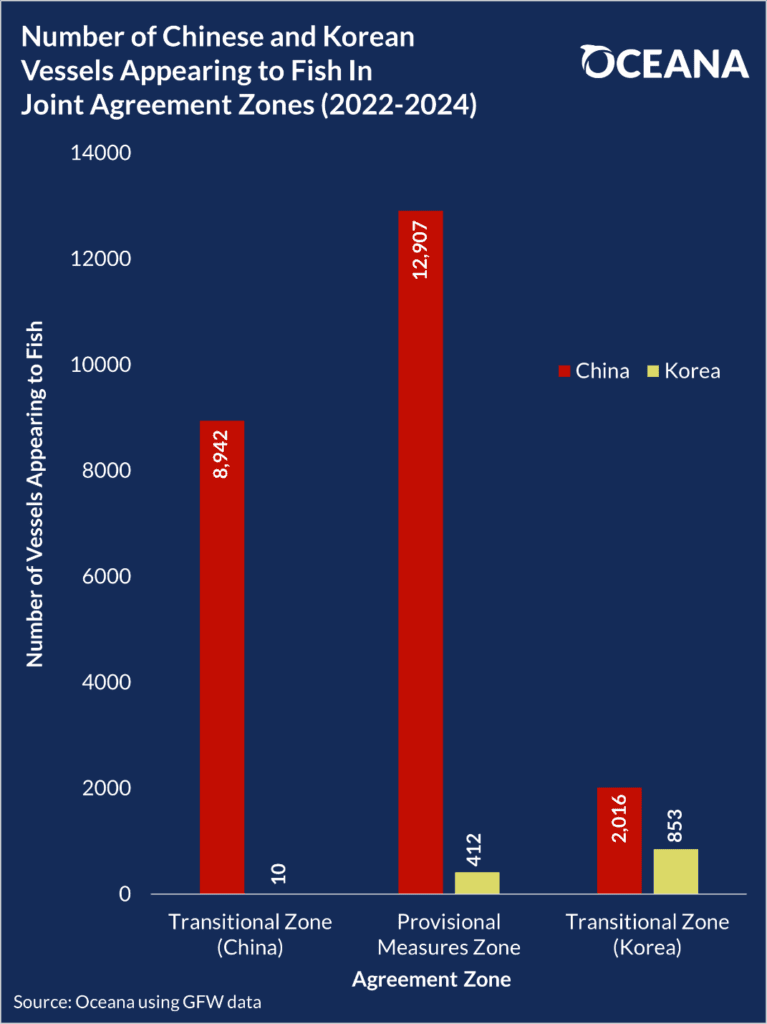

Using public data from Global Fishing Watch (GFW)** – an independent nonprofit founded by Oceana in partnership with Google and SkyTruth – Oceana compared the extent of Chinese and South Korean fishing activity in these disputed territories. Despite the shared nature of the PMZ, and despite the recent agreements to reduce fishing, China continues to dominate the fishing activity in these areas. In the three-year period between January 1, 2022 and December 31, 2024, South Korean vessels appeared to fish for just 66,267 hours in the jointly managed PMZ. Meanwhile, Chinese vessels appeared to fish for over 8 million hours – over 100 times more than South Korea. This is enabled by China’s massive fishing fleet, the largest of any country in the world (see Oceana’s fact sheet on China’s global fishing footprint). In the PMZ, China operated over 30 times as many fishing vessels as South Korea. Even in South Korea’s “transitional zone” where China should be scaling back its fishing, China outpaced South Korea’s apparent fishing hours by 36%, with over twice as many active vessels.

This analysis of GFW data is only possible because many fishing vessels broadcast their positions using Automatic Identification System (AIS) devices. Publicly available AIS data is essential to ensuring transparency at sea, maritime safety, and compliance with fishing regulations. However, not all vessels carry AIS devices or use them for their entire voyage, which means our analysis is only a snapshot of the entire fishing activity in this region. In 2023, in a huge step towards transparency at sea, China agreed to require all of its fishing vessels to carry and keep AIS devices on while in South Korea’s waters, which was implemented on May 1, 2024. This transparency mandate is an important step toward ensuring that fishing activity in the Yellow Sea is accounted for and compliant with international agreements in the years to come. With transparency comes accountability: vessels are accountable when we can see when, where, and how much they are fishing.

Oceana calls for governments and regional fishery management organizations to mandate that all fishing vessels carry and keep AIS devices on at all times.

————————————————————————————————————

*Any and all references to “fishing” should be understood in the context of Global Fishing Watch’s fishing detection algorithm, which is a best effort to determine “apparent fishing effort” based on vessel speed and direction data from the Automatic Identification System (AIS) collected via satellites and terrestrial receivers. As AIS data varies in completeness, accuracy and quality, and the fishing detection algorithm is a statistical estimate of apparent fishing activity, therefore it is possible that some fishing effort is not identified and conversely, that some fishing effort identified is not fishing. For these reasons, GFW qualifies all designations of vessel fishing effort, including synonyms of the term “fishing effort,” such as “fishing” or “fishing activity,” as “apparent,” rather than certain. Any/all GFW information about “apparent fishing effort” should be considered an estimate and must be relied upon solely at your own risk. GFW is taking steps to make sure fishing effort designations are as accurate as possible. All references to EEZ boundaries and sovereignty are based solely off the Marine Regions “World EEZ v12” definitions.

**Global Fishing Watch, a provider of open data for use in this article, is an international nonprofit organization dedicated to advancing ocean governance through increased transparency of human activity at sea. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors, which are not connected with or sponsored, endorsed or granted official status by Global Fishing Watch. By creating and publicly sharing map visualizations, data and analysis tools, Global Fishing Watch aims to enable scientific research and transform the way our ocean is managed. Global Fishing Watch’s public data was used in the production of this publication.

MOST RECENT

August 22, 2025

Corals, Community, and Celebration: Oceana Goes to Salmonfest!