August 17, 2017

Coastal Voices Part 4: Former Navy Acoustic Expert Fights Seismic Airgun Blasting

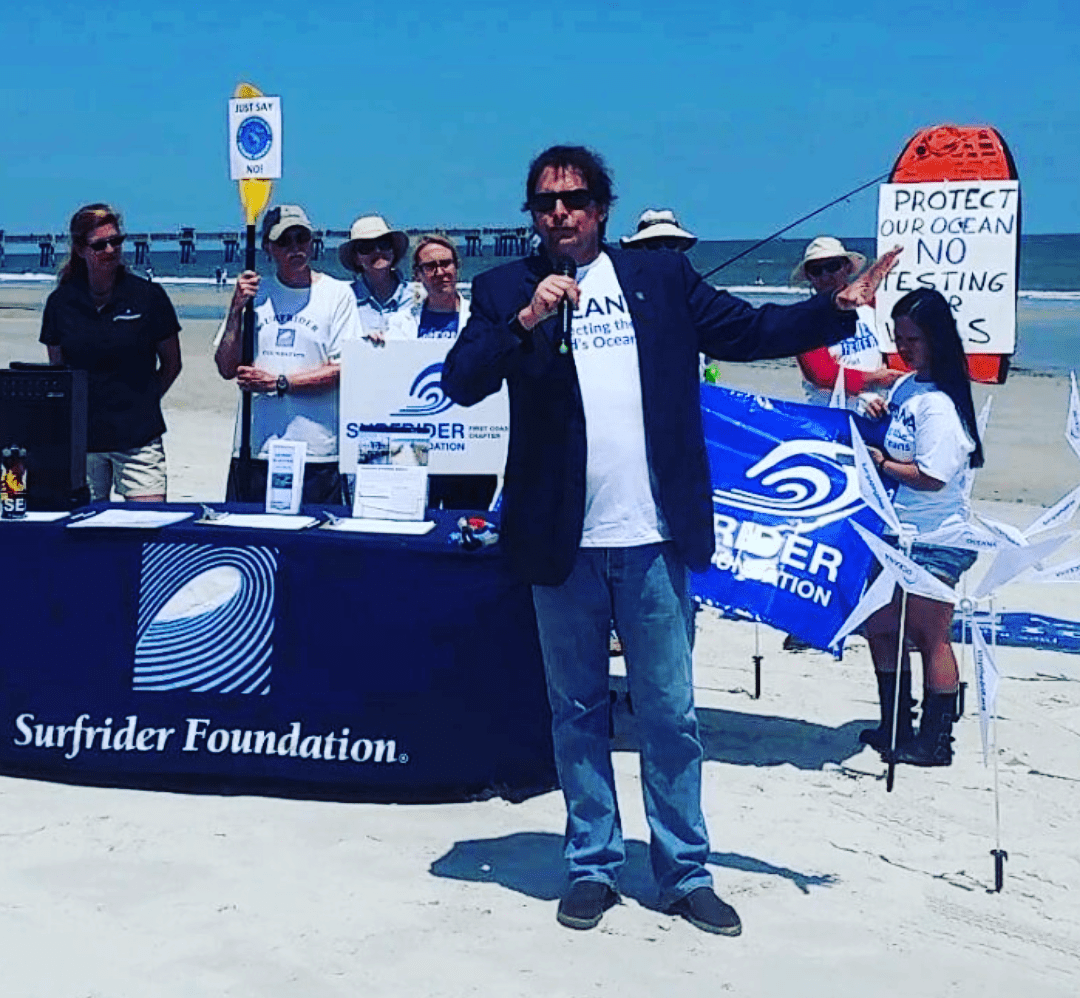

One of Johnny Miller’s first orders of business as city commissioner of Fernandina Beach, Florida, was to introduce a resolution against seismic airgun blasting — the process of using dynamite-like blasts of pressurized air to search for potential oil and gas deposits deep below the seafloor.

Miller first became interested in underwater acoustics and sound during his 20-year career in the U.S. Navy. He spent ten years as an acoustic sensor operator in submarine-hunting aircraft, a job that brought him intimate awareness about how important and powerful sound can be in the underwater environment.

When he heard that seismic airgun blasting was being considered off the coast of Amelia Island, where Fernandina Beach is located, he was alarmed.

Seismic airgun noise can be severely harmful to marine mammals that depend on their hearing, such as whales and dolphins. The sound can interrupt whale calls, alter their behavior and cause them to abandon their habitats, which can prevent them from feeding, migrating or reproducing.

This is especially concerning for baleen whales, such as the critically endangered North Atlantic right whale, of which about 500 animals remain.

“Almost everybody in my city is behind not having this happen off our coastline,” Miller said. “You can see the right whales from our beach, they’re that close. You can see dolphins going back and forth at sunset, at sunrise.”

“Knowing that they’re in danger from this is overwhelming to [our citizens], and they’re being very vocal about it.”

Miller connected with Oceana’s Florida campaign organizer Erin Handy. The two worked together and Handy gave the Fernandina Beach commission a presentation on seismic airgun surveys and offshore drilling.

Because of the town’s strong opposition, the resolution passed in 2014 with a 5-0 vote and Fernandina Beach became one of the first East Coast municipalities to formally oppose seismic airgun blasting.

Miller continued to advocate against seismic airgun blasting and offshore drilling, traveling to Washington, D.C., multiple times to speak to his representatives.

After the Obama administration removed the Atlantic Ocean from the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management’s five-year offshore leasing program in 2016 and denied the seismic airgun blasting permits in 2017, Miller and the residents of Fernandina Beach celebrated that the Atlantic was safe.

But then President Trump took office and put seismic airgun blasting back on the table along with expanding offshore drilling to the East Coast. Now, Miller is continuing his fight — not just for the marine mammals that would be affected by the noise — but also for the livelihoods that would be threatened by oil and gas drilling and exploration.

Many still rely on fishing for their livelihood in Fernandina Beach, with shrimping being especially important. Studies have shown that noise from seismic airgun blasting has resulted in 40 to 80 percent reduced catch rates in fish like Atlantic cod and herring, among others.

Miller also pointed to a recent study that a group of scientists conducted off the coast of Tasmania, which found that the noise from seismic airgun blasting can kill zooplankton from a distance of almost three-quarters of a mile away. The findings were published in Nature Ecology and Evolution.

“That zooplankton thing is really important because that’s a direct connection with fisherman,” Miller said.

Because zooplankton are an important part of the food chain, if their numbers were depleted due to seismic airgun blasting, it would also negatively affect the town’s fishers, Miller said.

Seismic airgun surveys simply indicate roughly where oil and gas might be. The only way to be sure is to drill exploratory oil wells, which continues to make noise and comes with additional consequences like leakage and spills, Miller said.

The BP Deepwater Horizon, which exploded and spilled millions of gallons of oil into the Gulf of Mexico, was an exploratory oil rig.

“While [the rig is] out there . . . they don’t just stop making noise when they stop blasting,” he explained, referring to the noises associated with drilling. “That sound in the water is going to be continuous forever and oh by the way, there’s oil washing up on our beach—our beach that brings in millions of dollars in tourism.”

“How can we do that, I mean how can we justify doing that?” he asked.

Tourism is a large part of Fernandina Beach’s economy, Miller said; its annual shrimp festival, for example, draws as many as 100,000 visitors. Along the East Coast, over $95 million in gross domestic product relies on healthy ocean ecosystems, mainly through fishing, tourism and recreation, according to an Oceana report.

Oil spills hurt tourism. After the BP Deepwater Horizon disaster, tourists who planned to go to Pensacola, the westernmost city in the Florida panhandle, for vacation went to Fernandina Beach instead, Miller said.

Oil from the BP disaster washed up on Pensacola’s beach, known for its white sand, prompting some tourists to say they wouldn’t return there for vacation, according to a Reuters article.

When tourists go back home, “they want to know that when they come back in 10 years it’ll be the same,” Miller said.

“In the back of their mind, at least they’ll know Amelia Island is still there.”

Miller said that while he can’t prevent natural disasters like hurricanes, he can help prevent another BP Deepwater Horizon disaster from happening in his backyard. But it’s also up to the people of the East Coast to get involved.

For those unsure of where to begin, Miller suggested starting with local government before moving onto Congress.

“If you’re in [Washington], D.C., go see your representatives,” he said. “If your community hasn’t passed a resolution, it should.”

And if you’re in Fernandina Beach, you can see Miller in his “office” – the Palace Saloon, the oldest bar in Florida where he still bartends. He can tell you all about how to get involved and stay involved.

“It’s really important to not quit and get out there.”

Next week, Queen Quet, chieftess of the Gullah/Geechee Nation, explains how seismic airgun blasting and offshore drilling threatens the livelihood of the Nation, which historically stretches from Jacksonville, North Carolina, to Jacksonville, Florida.

Follow the Coastal Voices series at usa.oceana.org/Coastal-Voices — help us share their stories.

MOST RECENT

September 3, 2025

Air Raid Panic to Informed Skies and Seas: The National Weather Service in a Nutshell

August 29, 2025

August 22, 2025

Corals, Community, and Celebration: Oceana Goes to Salmonfest!