August 4, 2016

Exploring and Discovering the Deep Sea

There is much about the deep ocean that still remains a mystery. Imagining life on the deep, dark ocean floor evokes a world of intrigue and possibility, a land on planet Earth that has yet to be fully explored. Sadly, this mysterious place could be under threat before mankind even has time to discover what lives and thrives there. Corals, sponges, and other living structures that decorate the seafloor support commercial species such as Pacific cod and other groundfish as well as various marine animals like octopuses and sea stars. It is therefore important for us to continue deep sea research and take a precautionary approach to managing activities that could threaten the health of these vital ecosystems and ultimately, the health of the world’s oceans.

Oceana will embark on an expedition this month off the coast of Southern California to do just that: explore and document the living seafloor, including undersea canyons, mountains, and rocky reefs and document the animals that rely on these deep-sea ecosystems. Using a Remotely Operated Vehicle (ROV) to examine the ocean floor, Oceana is particularly interested in exploring specific areas where little or no data exists and that are currently open to bottom trawling—the most damaging fishing method to seafloor habitats off the U.S. West Coast. Additionally, we will be looking at areas that have been protected from destructive bottom trawling to see how they compare. The goal of this expedition is not only to document unique and diverse habitats, but also to contribute to scientific discoveries and help secure protections not only for the treasures we have found, but also for fragile living seafloor habitats that have yet to be discovered. The ocean still holds a cache of unknowns—a global estimate published in 2012 predicts as much as 75 percent of all marine species have yet to be discovered, and a 2014 report finds that less than one percent of the ocean floor has been mapped to high resolution.

In the last few years, deep sea exploration uncovered new species previously unknown to science. These recent findings suggest that there is still so much to learn about the seafloor. Here are some of these new species:

Ghost Octopus

The ghost octopus is a very pale cephalopod (the family also belonging to squid), discovered 2.6 miles deep on Hawaii’s ocean floor. This octopus is different from many others for a few reasons: its ghost-like appearance, lack of fins, and gelatinous consistency. It is the deepest-dwelling organism without fins ever found!

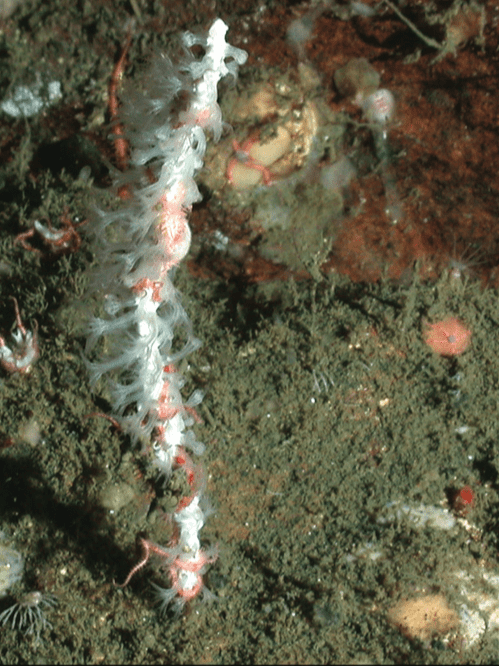

New Species of Coral

Swiftia farallonesica, a new species of coral named after the Greater Farallones National Marine Sanctuary where it was found, was discovered by biologist Gary Williams. Unlike the corals that form lush tropical reefs in shallow ocean waters, this coral is a 15-inch tall, solitary individual. Another interesting characteristic of this lonely creature is its method of feeding: it has a thousand mouths that eat microscopic plankton, which are brought in as ocean currents flow past the coral’s swaying stalk. This coral lives in a diverse and abundant environment along with other marine species that include sea stars, sea worms, snails, sponges, sea cucumbers, crabs, and at least 34 other types of fish.

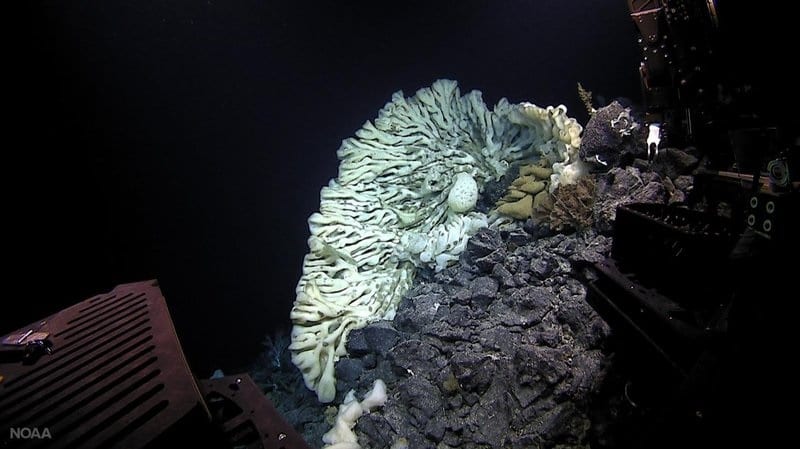

Minivan-sized Sponge

This minivan-sized sponge, found at a depth of 7,000 feet off the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, is the world’s largest documented sponge. This sponge, with a bluish-white color and a brain-like appearance, provides critical habitat for sea life and filters large amounts of seawater containing microscopic content that other animals don’t use. Some other large sponges found in shallower waters have been found to be over 2,300 years old, suggesting that this sponge could be of similar age. This finding shows how studying deep sea environments can lead to such extraordinary discoveries of species untouched by humans.

Killer Sponge

Four meat-eating sponges (Asbestopluma monticola, Asbestopluma rickettsi, Cladorhiza caillieti, and Cladorhiza evae) were discovered in deep waters off the coast of California by Lonny Lundsten, a biologist at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute. These carnivorous sponges feed on tiny crustaceans, such as shrimp, and are found mostly near undersea volcanoes and deep sea vents. Most deep-sea sponges capture food using choanocytes, which are cells with long, tiny tails that whip around and create wave-like currents to force single-celled organisms into the sponge’s system. These carnivorous sponges, however, have hooks located at the ends of tiny hairs that trap prey for food. Also, since the sponges lack a mouth to chew their prey, they rely on specialized cells that travel through the sponge’s body carrying specific enzymes that digest the food. These sponges’ harsh habitat may explain their tough lifestyle; found near volcanoes and vents where little food floats by, having choanocytes would be wasting precious energy.

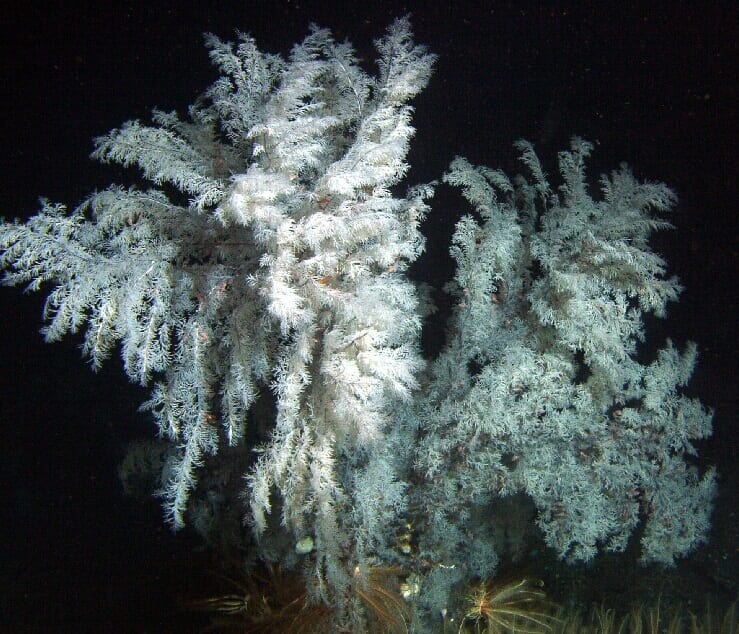

Christmas Tree Coral

The Christmas tree coral, Antipathes dendrochristos, was observed at 150 meters (492 feet) depth from a two-person mini-submersible Delta during surveys of benthic fish in the Southern California Bight—a large area where the coastline curves from Point Conception to the Mexico border. This coral can grow up to three meters (9 feet) in height and width and resembles a Christmas tree with its pink, red, gold, and white assemblages. This coral was also found teeming with juvenile rockfish, an iconic deep sea species off the Pacific West Coast. The Christmas tree coral supports diverse biological communities and has a long lifespan (50 to several hundred years), a slow growth rate, a low natural mortality rate, and limited larval dispersal. It is therefore highly vulnerable to disturbance from certain fishing gears like bottom trawls, and, if damaged, could take hundreds of years to recover. There are several predicted hotspots of Christmas tree corals that remain unprotected from fishing activities such as bottom trawling.

Longfin Gunnel

First described in 1964, the longfin gunnel, Pholis clemensi, was observed and identified by scientists reviewing HD video footage captured by Oceana from a ROV dive off north central California in 2011. Gunnels are small, elongated, laterally-compressed benthic fishes usually found living in shallow (less than 18 meters, or 59 feet) coastal waters in the North Atlantic, Arctic, and North Pacific Oceans. When Oceana scientists observed a longfin gunnel off Point Lobos, California, it was over 180 miles south of the previously presumed range for this species and at more than 30 meters deep, it was also twice as deep as its typical depth range.

As more ecologically important areas and species are discovered in the deep ocean, the question of protecting them arises. In July 2013, Oceana, and our conservation partners, submitted a conservation proposal to garner protections for the living seafloor in places where new scientific findings have come to light. This proposal defends the living seafloor protections that Oceana secured in 2005 and urges the protection of an additional 142,968 square miles of ocean habitat off the coasts of Washington, Oregon and California. In November, the Pacific Fishery Management Council will decide whether to adopt the proposal put forward by Oceana and partners, maintain the status quo, or select an alternative proposal that would result in a net conservation loss in regions up and down the U.S. West Coast. Denying necessary protections to these fragile deep sea ecosystems can lead to habitat destruction that could take hundreds of years to recover, if they recover at all. You can help protect the animals that call the deep sea home by signing this letter of support telling federal fishery managers you care about the health of the living seafloor and the health of the world’s oceans.

MOST RECENT

September 3, 2025

Air Raid Panic to Informed Skies and Seas: The National Weather Service in a Nutshell

August 29, 2025

August 22, 2025

Corals, Community, and Celebration: Oceana Goes to Salmonfest!