July 21, 2017

Oceana Files Suit Challenging Federal Failure to Protect Endangered Sea Turtles, Whales, Dolphins from California’s Deadly Swordfish Driftnets

On July 12, 2017 Oceana filed a lawsuit challenging the Secretary of Commerce and National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) decision to back out of a proposed rule establishing limits—called hard caps—on the injury and death of endangered whales and sea turtles entangled in the Californian-based swordfish driftnet fishery. The surprise retraction is a blow to state and federal fishery managers on the Pacific Fishery Management Council who voted to recommend the rule, state leaders who have been working to clean up California’s dirty driftnet fishery, and the tens of thousands of people who supported this action. What’s worse is that the 20 active driftnet boats now have a green light to continue to kill dolphins, sea lions, whales, turtles, sharks and many other animals as “bycatch” without limit or consequence.

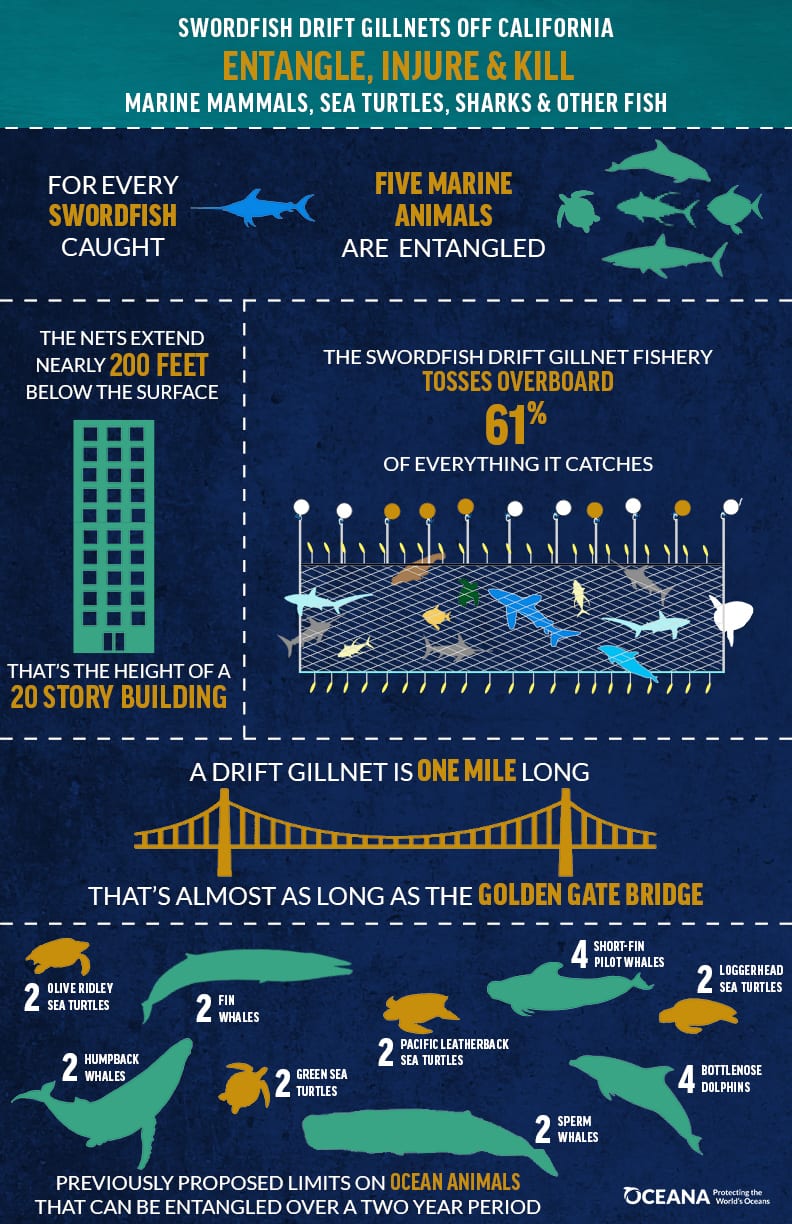

The Pacific Ocean off California is referred to by some as the Blue Serengeti because this exceptionally rich and productive ocean ecosystem is a migratory destination for massive herds of ocean animals that travel here to feed. Yet in the heart of this wildlife hotspot, fishermen pursue swordfish at night using mile-long nets that are nearly 200 feet deep.These driftnets are inherently unselective and have a long track record of entangling and killing whales, dolphins, sea lions, sea turtles and non-target fish including rare sharks, billfish and rays.

Image caption: The California swordfish drift gillnet fishery kills more dolphins than all other West Coast and Alaska fisheries combined. Photo: NMFS.

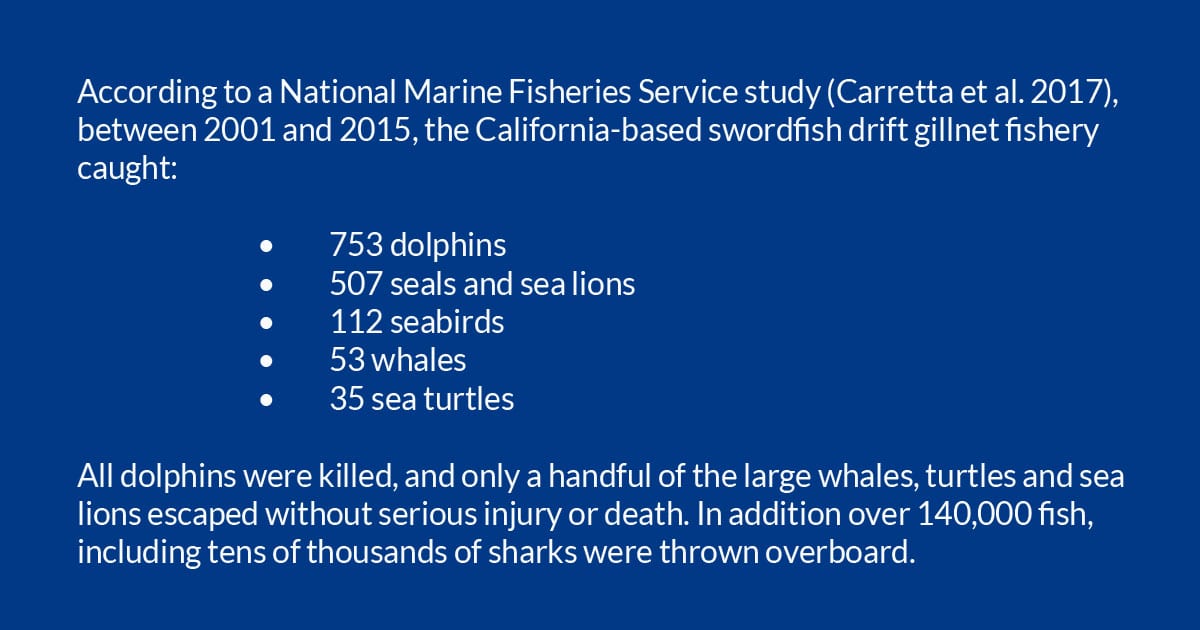

According to data collected by the National Marine Fisheries Service observer program, the fishery throws overboard, on average, more than 60 percent of its catch and kills valuable recreational fish like marlins as well as rare, sensitive hammerhead sharks, megamouth sharks, and manta rays. This single fishery kills more dolphins than all other West Coast and Alaska fisheries combined. NMFS estimates that between 2001 and 2015 the fishery entangled 1,460 marine mammals, sea turtles and seabirds (Carretta et al. 2017). These driftnets are widely known to be so dirty that no other U.S. region or state allows them to be used to catch swordfish. Internationally, driftnets are banned on the high seas, and swordfish driftnets are banned in the Mediterranean Sea.

While short of a ban on California’s swordfish driftnets that many have called for, in September 2015, the Pacific Fishery Management Council (Council) voted to set hard caps on the number of endangered fin, humpback and sperm whales, endangered leatherback, olive ridley, loggerhead and green sea turtles, plus common bottlenose dolphins and short-fin pilot whales that could be taken in the driftnet swordfish fishery. If a cap were reached for any of these nine species, the fishery would have closed for the remainder of the season, and possibly the following season as well. The Council also voted to establish new regulations requiring 100 percent monitoring of all driftnet vessels by 2018 and to remove an exemption the agency granted for a quarter of the fleet which it deems unobservable due to small vessel size. Currently, 80 percent of the driftnet fishing effort is unobserved, amounting to a significant and incomplete picture of the full extent of impacts to rare and sensitive marine life.

The Council expressed it’s “dissapointed with the NMFS decision to halt implementation of the hard cap rule.” The Council explained, “the hard cap rule was intended to provide an incentive to fishermen to further avoid interactions with protected species” and that the hard caps would promote “individual responsibility… communication and innovation by fishermen to avoid [protected species] interactions” (PFMC 2017).

While working to clean up driftnets, the Council is in the process of authorizing a new gear type — deep-set buoy gear — that is a clean alternative for selectively targeting swordfish. In experimental gear trials, 81 percent of deep-set buoy gear catch to date has been swordfish, 98 percent of the catch has consisted of marketable fish species, and all discarded species have been released alive.

Overall the Council’s plan would have helped develop a sustainable West Coast swordfish fishery by creating strong incentives to clean up the dirty driftnet fishery while providing new opportunities to develop and switch to selective fishing methods. The California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW 2015), which is represented on the federal fishery Council, proposed and supported the hard cap rule…

“CDFW believes that hard cap management is the most effective and appropriate mechanism to address bycatch reduction. It provides an incentive to continuously minimize bycatch of important species, a timely mechanism to close the fishery once a cap has been reached, and assurance that no additional bycatch will accrue in a given season.”

Despite voting for the action at the Council in 2015, NMFS reversed course last month by withdrawing the proposed rule that would have implemented the caps. The agency rationalized its decision by pointing to the potential for “significant adverse economic effects.”

The agency, however, failed to consider that the caps would be less likely to be reached as fishermen changed behavior —fished cleaner— and avoided setting their nets in locations likely to take endangered whales and turtles. The agency failed to acknowledge that if caps were reached, these same fishermen have opportunities to continue to participate in other fisheries like the albacore tuna, white seabass, or California halibut fisheries. What is more, the agency failed to consider the fact that many driftnet fishermen have experimental permits to use deep-set buoy gear, which would enable them to selectively fish swordfish even if the driftnet fishery were closed.

From an economic perspective, the value of California’s driftnet fishery landings (~$1.4 million per year on average) are only one percent of the total value of all of California’s commercial fishery landings. Compare those driftnet-caught swordfish to the value of California’s whale watching industry which, according to a 2006 study prepared for the National Ocean Economic Program, generates $20 million per year in gross revenue (Pendleton 2006). The same study finds the non-market value of marine wildlife viewing in California may be valued at hundreds of millions of dollars annually. Or, just compare California driftnet caught swordfish that fetch $4.34 per pound at the dock to deep-set buoy gear swordfish that get $8.75 per pound for a far superior, fresher catch. Clearly, the economic value of protecting and enhancing California’s ocean wildlife is significant, and it far surpasses the extractive value of driftnet-caught swordfish.

Given that for now, driftnets are being deployed off California without limits, what should happen next? It’s our view swordfish driftnets should be prohibited and the fishery should transition to using selective deep-set buoy gear and harpoons. In the interim, the Council’s proposed hard caps should be implemented, which is why we are challenging the agency’s withdrawal of the proposed rule. Until these driftnets are off the water, here are recommendations for consumers, businesses and fishery managers:

- Sign and share this petition urging the Assistant Administrator of NOAA Fisheries to end the use of deadly drift gillnets to catch swordfish off the California coast.

- Don’t buy swordfish caught with drift gillnets or pelagic longlines (which are equally destructive to ocean wildlife). If you are going to buy swordfish in California, seek out swordfish caught with harpoon or deep-set buoy gear instead.

- State and federal fishery managers should move forward with additional management actions, including:

- Authorize a limited entry deep-set buoy gear fishery with incentives to encourage driftnet fishermen to trade-in their drift gillnet permits and gear in exchange for deep-set buoy gear permits.

- Retire all latent swordfish driftnet permits (roughly 50 fishermen who do not actively fish have permits to use this gear. Current rules would allow these fishermen to resume using driftnet gear at any point).

- Phase out all active driftnet permits as fishermen retire or otherwise exit the fishery.

- Require 100 percent monitoring of all catch and bycatch in all driftnet fishing vessels and remove the unobservable fishing vessel exemption.

- Maintain all existing areas closed to driftnets and implement new measures to prevent any increase in driftnet fishing effort and to control and reduce bycatch.

- Implement import restrictions on foreign swordfish products that do not meet U.S. bycatch standards to level the playing field for U.S. fishermen.

Sustainable ocean fishing is in the best interest of all of us. In this case, these same fish can be caught with other gear that won’t damage our oceans by catching dolphins, whales, and sea turtles. The answer is clear. It is time to stop the nets.

Citations:

CDFW 2015. California Department of Fish and Wildlife Report on Swordfish Management and Monitoring Plan. Pacific Fishery Management Council Agenda Item G.2.a Supplemental CDFW Report September 2015, at page 5.

Carretta, J.V., J.E. Moore, and K.A. Forney. 2017. Regression tree and ratio estimates of marine mammal, sea turtle, and seabird bycatch in the California drift gillnet fishery: 1990-2015. NOAA Technical Memorandum, NOAA-TM-NMFS-SWFSC-568. 83 p.

PFMC 2017. Pacific Fishery Management Council News. Summer 2017. Page 8. www.pcouncil.org

Pendleton, L. 2006. Understanding the Potential Economic Impact of Marine Wildlife Viewing and Whale Watching in California: Executive Summary. Lead Non-Market Economist. National Ocean Economic Program.

MOST RECENT

September 3, 2025

Air Raid Panic to Informed Skies and Seas: The National Weather Service in a Nutshell

August 29, 2025

August 22, 2025

Corals, Community, and Celebration: Oceana Goes to Salmonfest!