April 12, 2016

The Role of Fishing in the Pacific Sardine Collapse

Authored by: Geoff Shester and Ben Enticknap

In the Pacific Ocean off the U.S. West Coast sardines play a vital role in sustaining a healthy ocean food web and at times they have supported an economically booming fishery. These small fish normally spawn in the spring off southern and central California and then migrate in large schools to rich coastal upwelling regions off Northern California, Oregon, Washington and Vancouver Island, where they feast on plankton. Sardines are relatively short-lived fish, with few of them living longer than six years. Many of them end up being eaten by pelicans, sea lions, tuna or whales; or being caught in commercial fishing nets, frozen, and sent around the world to be used to feed penned tuna, packed into a can, or used as bait. In the ocean, sardines are part of a larger group of tiny fish, called forage fish, which are food for fish and animals higher up on the food web.

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Marine Fisheries Service (NOAA Fisheries) 2016 sardine assessment, the Pacific sardine population took a nose dive and dropped by roughly 90 percent between 2007 and 2016. In response to this crash, in April 2015 the federal Pacific Fishery Management Council voted to close the directed commercial fishery. This week, the Council voted to keep the fishery closed for another year.

The science is clear: the population crashed. There is continued debate, however, surrounding the drivers of the crash and whether or not changes should be made to how the fishery is managed in the future.

Oceana agrees that this sardine decline is related to changing environmental conditions, but we believe the decline was exacerbated by overfishing. Excessive fishing rates on an already crashing population increased the rate and magnitude of the decline and this further impacted already struggling predators like California sea lions and brown pelicans that rely on abundant forage fish populations for food.

Here are some basic facts about the sardine crash, the role of fishing, and advice for managers for how to prevent this unfortunate situation from occurring again in the future:

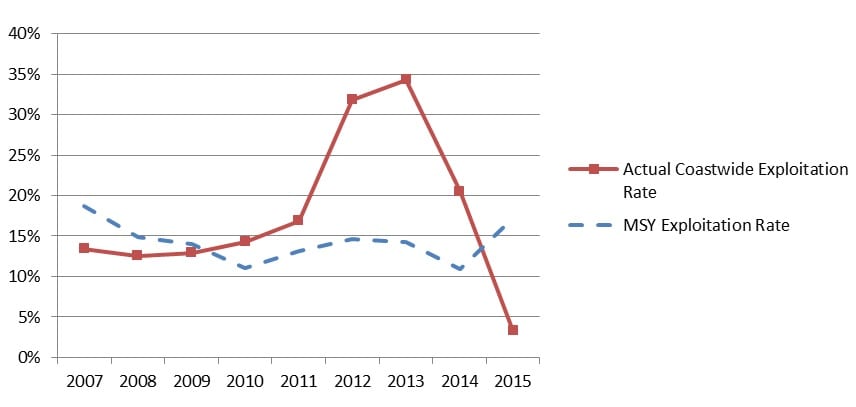

By July 2016, the sardine population will have declined by over 840,000 metric tons (mt) (1.8 billion pounds) since 2007. Coast-wide (U.S., Mexico and Canada) commercial fishing rates significantly increased during the time the sardine population was crashing. U.S. and coast-wide fishing rates exceeded maximum sustainable yield, which is the maximum amount of fish that can be removed from the ocean while allowing the population to naturally replenish. For example, in 2013, coastwide fishing removed 34 percent of the entire population, over double the maximum sustainable yield.

By definition, this is overfishing.

Figure 1. Evidence of overfishing. Coastwide (Mexico, U.S. and Canada) sardine exploitation rates exceeded maximum sustainable yield (MSY) exploitation rates five out of the past nine years during the sardine decline. Managers closed the Pacific sardine fishery early in April of 2015 and voted to maintain the commercial fishery closure throughout the entirety of the 2015-16 and 2016-17 fishing seasons. Exploitation rates are from the NOAA Fisheries 2016 sardine assessment.

NOAA Fisheries maintains that managers did not intentionally allow overfishing of the stock. And although U.S. fishing levels did not exceed U.S. overfishing limits set at the time,, the 2016 assessment clearly shows that those overfishing limits were set too high based on how the Council’s Scientific and Statistical Committee now calculates maximum sustainable yield. We now know that excessive fishing rates were caused by a combination of overly optimistic estimates and other scientific errors. Importantly, managers failed to heed the warning signs made obvious by starving sea lions washing onto southern California beaches and by scientists who predicted the sardine collapse.

In 2012 two federal and academic fishery scientists published a scientific study predicting the sardine collapse and warning managers of increasing exploitation rates targeting the oldest, largest and most productive fish. Unfortunately, the study received a chilling response. In a letter to the Council, NOAA science leaders advised that the Council disregard the study, stating that the Pacific sardine population “… is not currently in a state of imminent collapse as referenced in the [Proceedings of the National Academy of Scientists] article of March 2012.”

Sadly, those two scientists who predicted the crash turned out to be right. Three years later the sardine assessment confirmed the population crashed and managers had to close the fishery. Still, some assert the crash was entirely driven by changing oceanographic conditions.

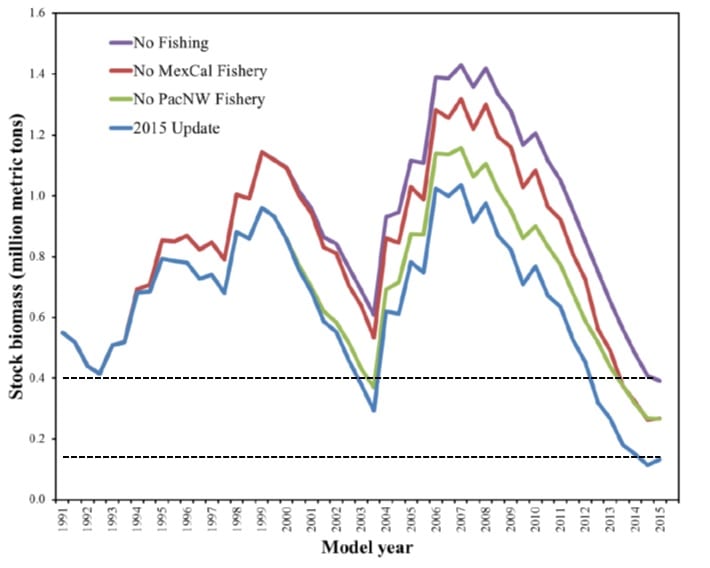

At the April 2015 Council meeting, a NOAA Fisheries scientist presented an analysis of what the sardine population might look like in the absence of fishing. This analysis shows that, due to unfavorable ocean conditions and thus the lack of recruitment, the population would have declined in the absence of fishing. But it also shows the population would be almost four times higher than it is now if fishing had not occurred. In other words, the analysis shows that fishing made the sardine decline worse. Consistent with published scientific studies on the effects of fishing on forage fish and the vulnerability of forage fish to fisheries collapse, it is clear fishing has exacerbated the sardine population collapse.

Figure 2. Figure by NOAA Fisheries scientists shows that fishing has made the current sardine population roughly four times lower than it would have been in the absence of fishing. The population in 2015 without fishing would have been approximately 400,000 metric tons (purple line, “no fishing”) versus the estimated 96,688 metric tons (blue line) in the 2015 assessment.

Another recent scientific publication finds that the lack of “high quality” forage fish – both sardine and anchovy – available to breeding female sea lions is the reason California sea lion pups are starving and, “ultimately flooding animal rescue centers with starving sea lion pups.” The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is finding that brown pelicans are abandoning their nests and failing to breed due to a lack of forage fish, namely sardine, anchovy, and mackerel. So in summation, overfishing during the population crash caused the sardines to drop to lower levels than they otherwise would have been and the lack of sardine and other forage fish has been identified as the root cause for why sea lions are starving and brown pelicans are failing to reproduce.

Given the sardine fishery is now closed for another year, it is a good time to take a hard look at this issue, learn from past mistakes and from a growing body of scientific literature that indicates there are better ways to manage forage fish like sardines. The Lenfest Forage Fish Task Force recommends applying a catch formula where commercial fishing for a forage fish would be closed when it reaches 40 percent of its average unfished population size. Another study (“third for the birds”) identified that if forage fish populations decline by one third of their unfished population size, then seabirds experience impacts due to a lack of prey.

Under the current Pacific sardine rule, however, managers do not close the fishery until the sardine population has dropped to less than 10 percent (150,000 mt) of its average unfished population size. Consistent with the Lenfest Forage Fish Task Force recommendations, we propose increasing the minimum population limit or “cutoff” to 640,000 mt (40 percent of the average unfished sardine population size). This would prevent overfishing when the population reaches low levels and it would better account for the needs of dependent predators by providing a forage reserve.

While nobody knows for certain when the sardine population will recover, we must conserve the remaining sardine spawning population now so that when conditions are again productive, sardines can quickly rebound. Some Pacific sardine studies find that higher levels of fishing during stock declines worsen stock collapses and delay recovery. After seriously overfishing the sardine population in the 1940s and 1950s it took decades for sardine to rebuild and for the fishery to resume (late 1980s).

Managers must heed warning signs and learn from past mistakes to better manage the sardine fishery now and into the future. The fishing industry, the ocean ecosystem, and the public all will reap the benefits.

MOST RECENT

August 22, 2025

Corals, Community, and Celebration: Oceana Goes to Salmonfest!