August 11, 2017

Shark Fact Friday #12 – Super Scales

Welcome to Shark Fact Friday, a (mostly) weekly blog post all about unique sharks and what makes them so awesome. This week’s post is about shark scales.

If you were asked to describe a fish right now, what are the things you would think of? Probably that they live in the water, breathe using gills and swim with their fins. You might also say that fish bodies are covered in scales.

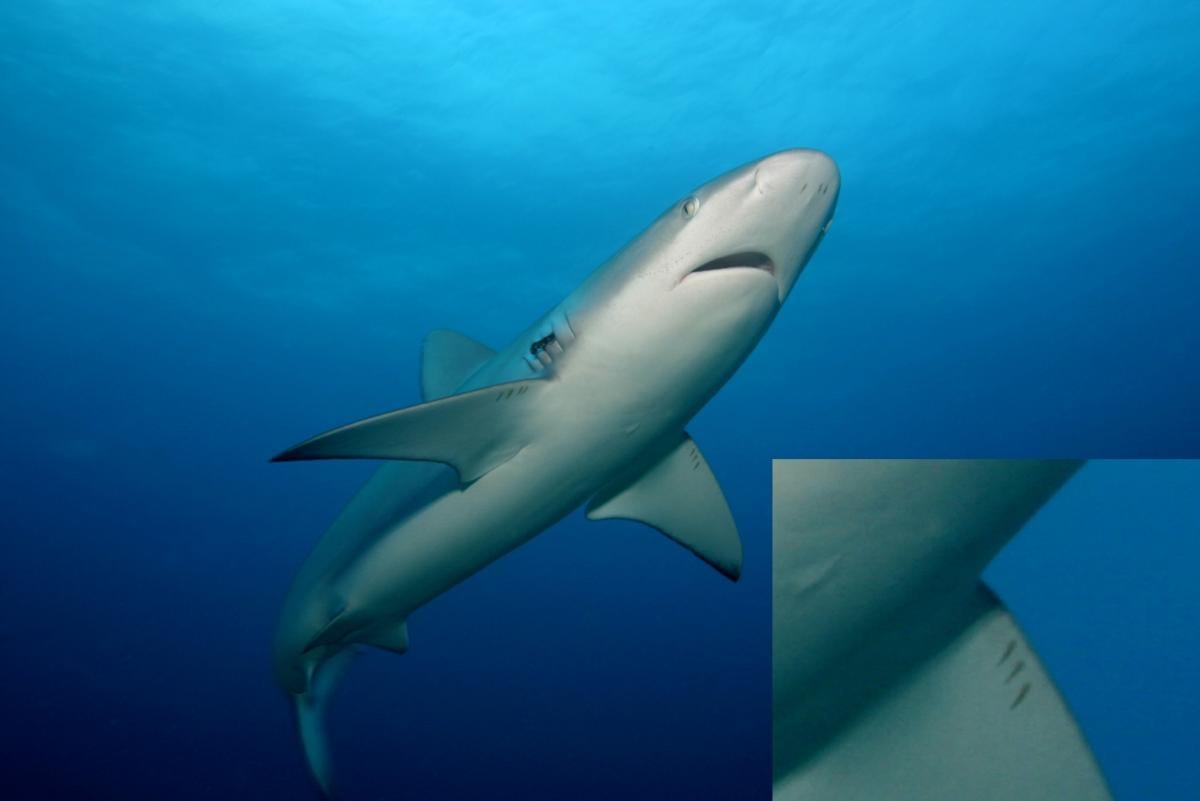

Did you know that sharks, just like other fish, have scales, too? But unlike other fish their scales are called dermal denticles, which translates into “small skin teeth.”

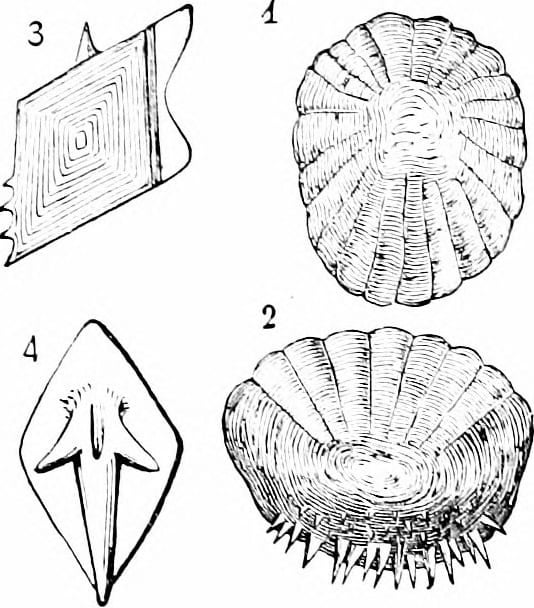

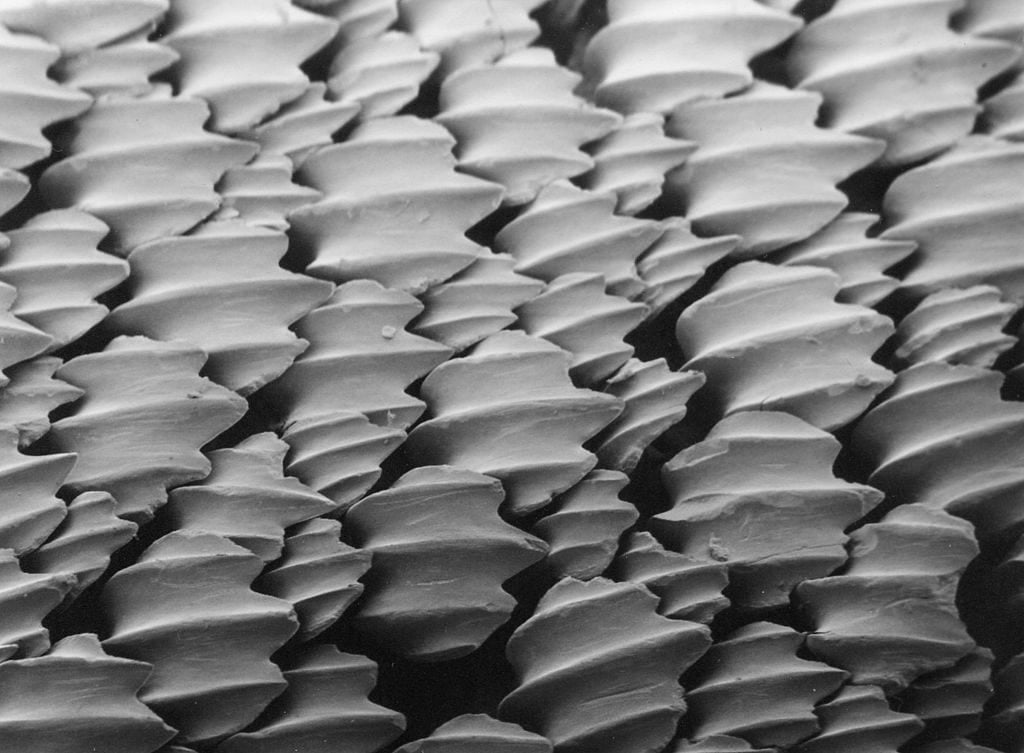

“Small skin teeth” sounds creepy, but it’s a great description for what these scales look like under a microscope. The scales are attached to the skin at the base, while the top, visible, part is called the “crown,” just like the crown of a tooth. The crowns generally end in a pointy tip that faces towards the tail, which is why shark skin is smooth when you rub it from head to tail, but rough when you rub from tail to head. In fact, these scales are so rough that the ancient Greeks used shark skin as sandpaper to smooth wooden objects.

So why are they shaped like that? These special scales have several functions that help sharks go about their lives in the ocean.

Probably the most obvious function is that these thick, hard scales are used to protect a shark’s skin. Sharks can encounter things in the ocean that can scrape them like coral reefs, rocky areas and marine litter like leftover fishing gear. Their tooth-like scales ensure that it’s not easy to scratch a shark.

Their scales also serve as their first line of defense against parasites. Sharks encounter parasitic worms, leeches, mites, barnacles, sea-lice and many others. These parasites can attach to the eyes, gills, mouth, stomach, heart, brain, and of course, the skin. It’s been hypothesized that the scales of sharks serve as a barrier between sharks and these parasites, however that doesn’t stop them all. Some parasites have adapted specifically to bury into and underneath the scales to get their meal.

The ridges on shark scales also help channel water flow towards or away from different parts of the body. In fact, it’s been shown that scales can direct water toward the nostrils, away from the eyeball surface and away from openings in the skin that contain electro-sensing organs that help sharks pick up on electric fields to find prey and magnetic fields that allow sharks to know where in the ocean they are.

Last, but not least, these special scales are specifically designed to help sharks move through the water. If you’ve ever tried to run through water, you have experienced something called “frictional drag,” which makes it hard to make headway. That’s because there is more friction between you and water than there is between you and air, and the force of that friction slows you down. The same thing applies to sharks; they exert a lot of energy trying to overcome the friction between themselves and water. However, the v-shaped grooves in their scales can reduce frictional drag up to 13 percent, making it easier for sharks to slice through the water.

With so many important functions, it’s easy to say that evolution certainly tilted the scales in sharks’ favor.

MOST RECENT

September 3, 2025

Air Raid Panic to Informed Skies and Seas: The National Weather Service in a Nutshell

August 29, 2025

August 22, 2025

Corals, Community, and Celebration: Oceana Goes to Salmonfest!