October 11, 2016

Soaring into the Sky in the name of Whales

BY: Oceana Admin

Authored by Albertha Ladina

Albertha Ladina (me) conducting an aerial survey over Monterey Bay.

On June 16, 2016, I may have had the greatest 21st birthday ever! Only four days into my internship with Oceana, I hopped on a tiny one-engine Cessna 182 with Dr. Geoff Shester, Oceana’s California Campaign Director to conduct an aerial survey counting fishing traps over Monterey Bay with LightHawk, a nonprofit organization that coordinates flights to collect data in support of conservation efforts. We were so lucky to work with a knowledgeable and helpful volunteer pilot, Bill Rush, who has been flying his whole life and calmed our fears about the possibility of an “off-airport landing” into the cold, dark Pacific Ocean. The flight was smooth and all of our worries dissipated as we soared up 1,000 feet into the clear, blue sky and gazed out over the picturesque Monterey Peninsula. Although I wanted to stare out of the window all day in awe, as soon as we flew over the water it was time to put on our research hats and begin collecting and recording data.

Aerial view of the Monterey Peninsula. Photo credit: Oceana/Geoff Shester

The purpose of our aerial expedition was to collect information on the number and spatial distribution of crab traps in the Monterey Bay to begin assessing the co-occurrence between fishing traps and large whales. Since January 2014, there has been an increase in the number of reported whales entangled in fishing gear, primarily traps used to catch Dungeness crab. In response, the state of California convened a Dungeness Crab Fishing Gear Working Group comprised of fishermen, government agencies, and non-government organizations including Oceana. Last year, this Working Group recommended testing tools to collect information to better understand the risk of whale entanglements in Dungeness crab fishing gear. One of these tools was to evaluate the potential for aerial surveys to collect more precise data on the distribution of fishing gear in relation to areas of high whale density. In May 2016, two working group participants conducted an initial flyover off California’s Central Coast to determine what types of data can be collected on aerial surveys, concluding it was possible to count and identify trap buoys. Building off their experience, and with additional advice from federal NOAA experts that conduct aerial surveys of ocean wildlife, Oceana scientists put together a new method to get the first of its kind glimpse into the number and distribution of crab traps in Monterey Bay. We focused on Monterey Bay because the California Department of Fish and Wildlife issued a voluntary advisory, with the support of the fishing industry and Working Group, to reduce the number of traps in the Monterey Bay area, particularly the edge of Monterey Canyon.

A group of dolphins found splashing around, seen from 1,000 feet. Photo Credit: Oceana/Geoff Shester

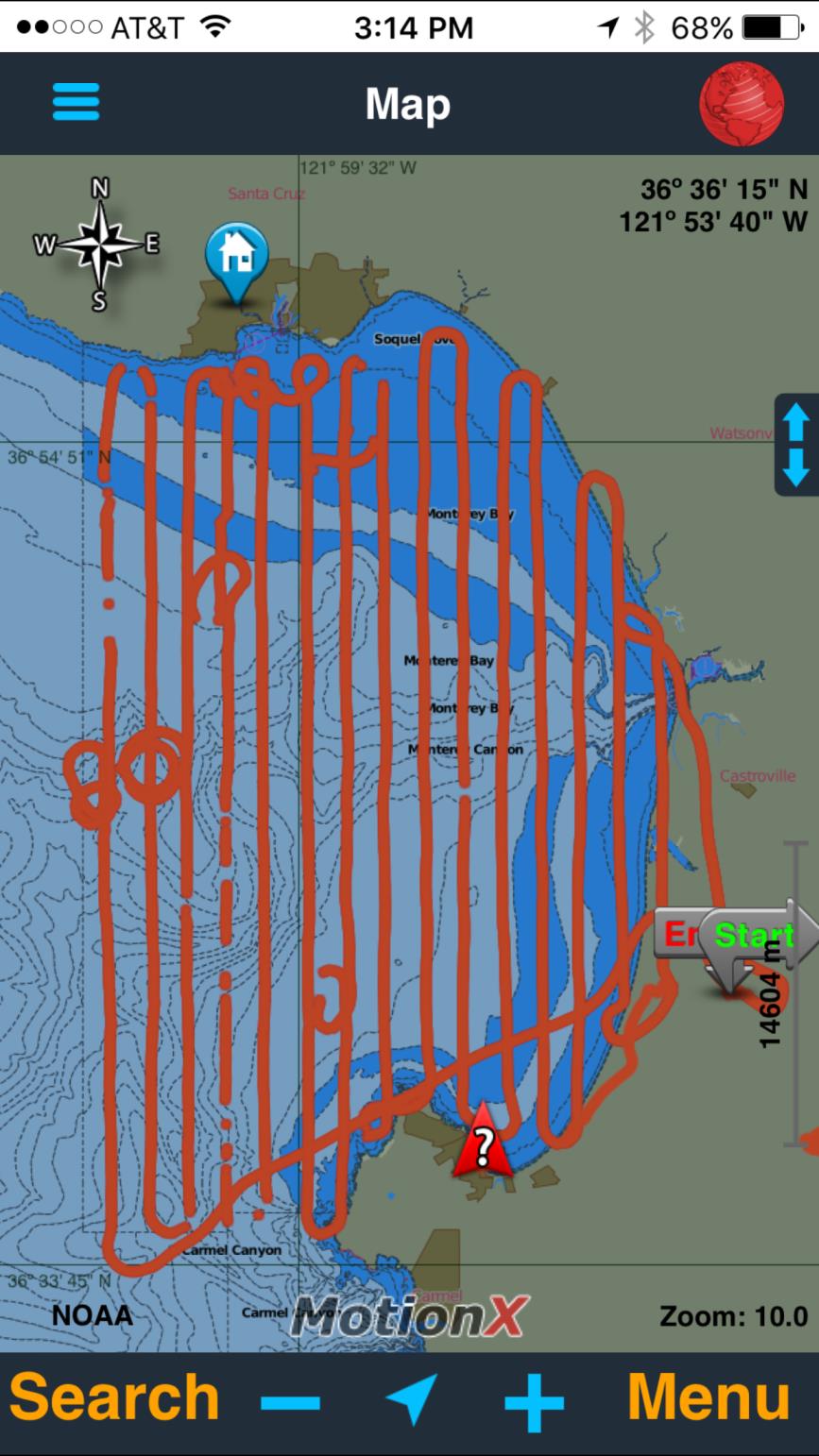

Bill controlled the plane ensuring we were evenly flying over 15 North-South transects spaced one mile apart, similar to “mowing the lawn” as shown in the picture below. I sat co-pilot recording data and taking GPS locations of every trap we saw. Geoff sat in the back of the plane and called out the traps he spotted and their respective position readings with a clinometer—an instrument that measures an object’s angle of inclination from the horizon. We later used this to estimate how far away each trap was from the transect line.

Screen shot of the iPhone app Motion-X GPS showing the full flight path over Monterey Bay. The circles show places we paused to watch wildlife and take photos.

Everything was going smoothly until it wasn’t. During the middle of our third transect, the laptop stopped working rendering us unable to record our information on the software. Fortunately, we were prepared for some hiccups and came prepped with a backup iPhone app called Motion-X GPS and some good old pen and paper. By and by, Geoff was able to distinguish traps and was able to quickly and effectively read out the respective angles. After the expedition, we were so confident in our observing and recording skills that we began discussing how to expand and replicate our methods to look at a wider geographic area and determine changes over time.

Flying at the low altitude of 1,000 feet over Monterey Bay was absolutely breathtaking; I found myself staring out of the window any chance I got. We were high enough to get a sense of how the Bay is structured, yet low enough to see and count individual marine animals and fishing buoys. We flew as far north as Santa Cruz on one end of the transect and as far south as Monterey only a few minutes later. At the same time, our 1,000-foot elevation gave us the opportunity to catch a few glimpses of spectacular wildlife. Now I know why scientists refer to this special place as a “Blue Serengeti” —it literally felt like we were on a safari. We saw tons of dolphins and molas—also called ocean sunfish—and even got a chance to spot a couple of humpback whales. We would momentarily “pause” the transect when we spotted wildlife and circle back to their location to admire the beautiful creatures.

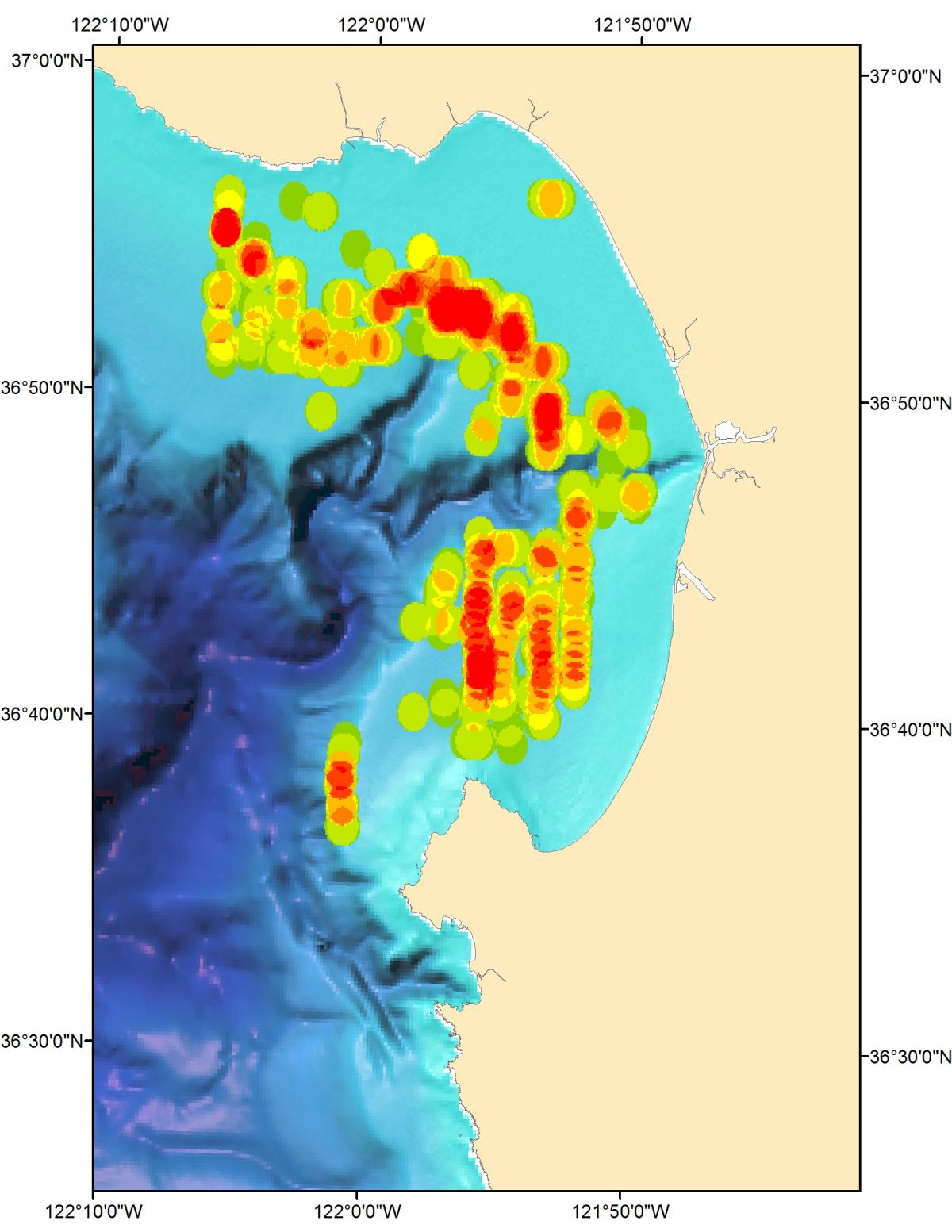

In total, we flew 314 miles of transects over an area of 353 square miles, and recorded 594 traps. After we returned, we plotted on a map all the traps we saw, and were able to show the locations and water depths where traps were most abundant in the Bay. Most traps ranged between 100 to 300 feet below the ocean surface.

Point density analysis of observed traps, with red areas showing hotspots of trap density within Monterey Bay.

Because of the systematic way we collected the data, we were also able to use a technique called “distance sampling” to estimate the total number of 2,086 traps in the Bay (95 percent confidence interval of 1,241-3,507). Recently, Geoff presented the results to the Dungeness Crab Fishing Gear Working Group, which welcomed the new information and agreed this was a promising tool. In concert with other projects to reduce whale entanglements by modifying how fishing gear is deployed, the Working Group is investigating ways to expand the use of this new tool next fishing season to cover a larger geographic area, include counts of whales, and repeat the survey throughout the season. A copy of the final summary report from the project can be downloaded here.

I owe Oceana and LightHawk a thousand thanks for the incredible opportunity to participate in such an extraordinary study. I am so grateful to have had the chance to learn about and participate in the creation of new survey methods to scientifically assess the co-occurrence between whales and crab traps to help identify collaborative solutions so we can have whale-safe fisheries here in California. Flying over Monterey Bay with Geoff and Bill in that tiny plane was an experience that I could never forget, and it was all in the name of ocean conservation. Who knew saving our oceans could be so cool?

Geoff using an inclinometer to measure the angles of the traps, a proxy for their distance from the plane.

Aerial View of Moss Landing, a town in the center of the Monterey Bay. Photo credit: Oceana/Geoff Shester

An example of a crab trap, highlighted by the yellow circle. Photo credit: Oceana/Geoff Shester

Aerial photo of Santa Cruz, the most northern point of the transects. Photo credit: Oceana/Geoff Shester

Aerial view of Pleasure Point, Santa Cruz. Photo credit: Oceana/Geoff Shester

MOST RECENT

September 3, 2025

Air Raid Panic to Informed Skies and Seas: The National Weather Service in a Nutshell

August 29, 2025

August 22, 2025

Corals, Community, and Celebration: Oceana Goes to Salmonfest!