The Modern Day Pacific Sardine Collapse: How to Prevent a Future Crisis

Open this page as a printer friendly PDF.

High in omega 3-fatty acids, Pacific sardines belong to a category of small, schooling fish known as forage fish because they are a critical source of food for many larger species.

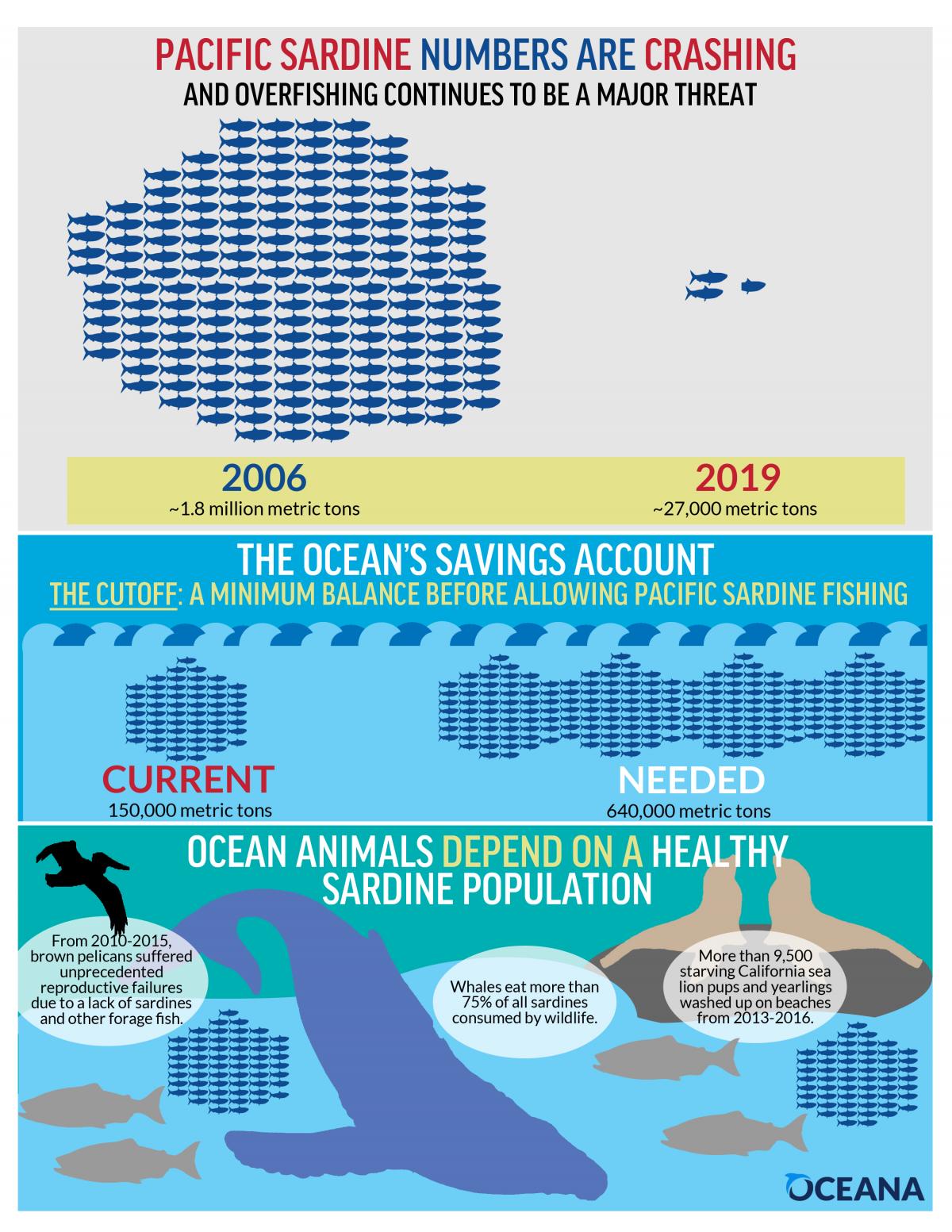

From whales, sea lions, and Chinook salmon, to brown pelicans, common murres, and least terns, Pacific sardines are an essential component in the diets of many ocean animals. These important forage fish have also been the target of commercial fishing dating back to the early 1900s, contributing revenue to the coastal economy and supporting fishing families.

Historically, sardine fishing with large purse-seine vessels peaked off California in the late 1930s, and then declined rapidly in the 1940s driven by oceanographic changes and excessive fishing pressure. The Pacific sardine fishery was closed from 1967 to 1986 and then in the 1990s, sardine landings started to increase again as the population recovered. By 2012, scientists warned the sardine population was again collapsing as ocean conditions changed and fishery exploitation levels were peaking. By 2015, a moratorium on U.S. commercial sardine fishing was once again implemented.

This is the story of the modern day collapse, lessons learned from past mistakes, and how to manage for a sustainable fishery while protecting the health of the ocean ecosystem.

EXCESSIVE FISHING RATES TO BLAME FOR SEVERITY OF PACIFIC SARDINE CRASH

The Pacific sardine population collapsed and the fishery was taking too many fish during the decline

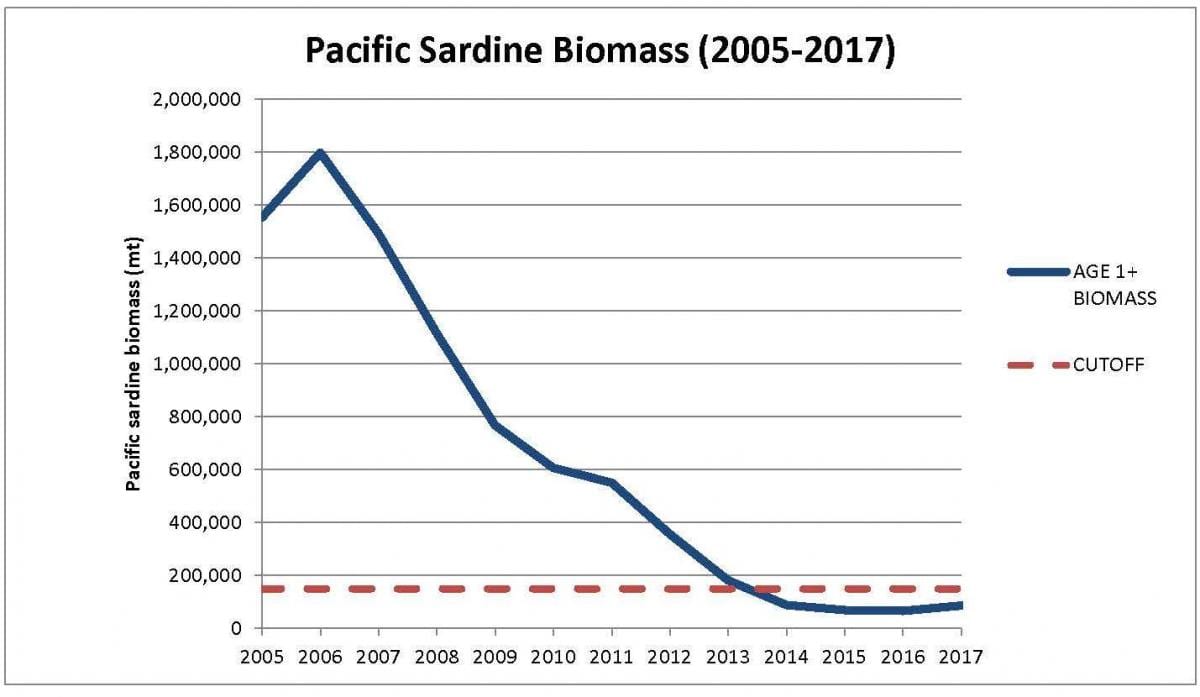

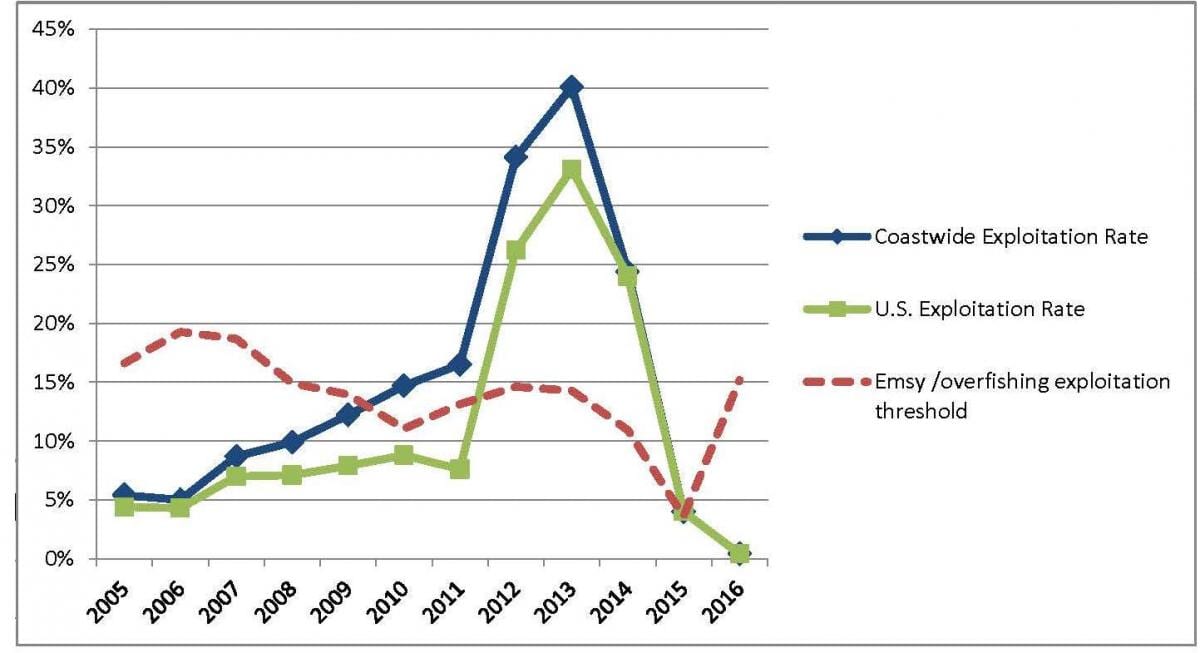

According to the most recent National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) assessment, the 2017 West Coast Pacific sardine population has crashed by 95 percent since 2006 to its lowest level in decades from 1.8 million metric tons down to just 86,000 metric tons (figure 1). Our review of the data shows that the sardine fishery was taking fish faster than the population could replenish itself between 2010 and 2014, exceeding sustainable levels (figure 2). In response to Oceana’s request for emergency action, the U.S. commercial sardine fishery was closed in 2015. For the third year in a row, there are not enough fish to allow for a commercial sardine fishery in U.S. waters.

While the sardine population naturally fluctuates in response to changing ocean conditions, fishing can increase the frequency and intensify the magnitude of forage fish collapse. A study published in 2015 directly found that fishing pressure worsens natural population-level collapses of forage fish species.

Figure 1.The Pacific sardine population has declined 95 percent since 2006 and it is now below the minimum level required to support a commercial fishery (called the “cutoff”).

The effects of the sardine collapse are reverberating through the food web

More than 9,500 California sea lion pups and yearlings stranded on beaches from 2013-2016, overwhelming marine mammal rescue centers in unprecedented numbers. Federal scientists concluded that insufficient availability of nutrient-rich forage fish left sea lion moms unable to produce enough milk to feed their pups and moms spent more time away from their pups in search of food. The lack of forage fish—including sardines—left the young mammals emaciated, dehydrated, and malnourished. Many sea lions died before they could be admitted to rescue centers. In 2013 and 2014, for example, it was estimated that about 70 percent of California sea lion pups died before weaning age due to a lack of nutrients.

Brown pelicans are feeling the effects too. Delisted from the Endangered Species Act in 2009, California brown pelicans breeding in the Channel Islands have suffered a decline in reproductive success since around 2007, culminating in major nesting failures in 2012-2014. Brown pelicans feed on northern anchovy and sardine, and with both fish populations simultaneously at low abundance, adult pelicans are starving and they are either not breeding or abandoning their nests due to a lack of prey necessary to sustain their chicks. A long term decline of sardine and anchovy may have serious impacts on the California brown pelican population and could send these birds back on the Endangered Species List. While the effects of a lack of food fish are most visible with sea lions and pelicans, there are likely many other wildlife species also nutritionally stressed.

THE PACIFIC SARDINE FISHERY MUST REMAIN CLOSED

In response to the 2015 population assessment and Oceana’s request for emergency action, federal fishery managers closed the directed sardine fishery in April 2015 and it has since remained closed. At this time, the sardine fishery must remain closed to allow this critical forage fish population to recover sufficiently to sustain itself and provide for dependent predators.

Only minimal levels of incidental catch of sardines are allowed so that other fisheries, including those for squid and mackerel, may continue to operate. Caps on incidental catch in other fisheries are necessary to ensure fishermen have a strong incentive to avoid catching any sardines.

These safeguards should remain in place until the population recovers to healthy levels.

PREVENTING A FUTURE CRISIS

Currently, the fishery must close when the population of sardines falls to 150,000 metric tons or less. Fishery managers call this the cutoff. This means fishing does not stop until the population has been depleted to about nine percent of average unfished levels.

Scientific studies show that a higher cutoff provides more forage fish for marine wildlife like whales and seabirds, prevents forage fish collapses, and maintains long-term sustainable catch levels in the commercial fishery. We have requested fishery managers increase the cutoff to at least 640,000 metric tons so that the fishery would close before reaching such dangerously low levels where the population has difficulty recovering and ocean wildlife suffers. Like a minimum balance on a savings account, no directed sardine fishing should be allowed when the sardine population drops below this cutoff.

This management change would minimize the risk of future overfishing while continuing to allow high levels of commercial sardine harvest when the population is healthy and abundant.

Preventing an International Tragedy of the Commons

The Pacific sardine population ranges from Baja California, Mexico to British Columbia, Canada. While all three nations fish this shared sardine population, management is not coordinated. The U.S. harvest plan assumes 87 percent of the population is in U.S. waters, 13 percent is off Mexico and zero percent appears off Canada. Canada assumes anywhere between seven percent and 33 percent of the population migrates into its waters, and in some years the two nations have taken more than half the catch from this population. As a result, the sum of all three nations’ catch exceeded the maximum sustainable yield—the amount of fish that can be removed without jeopardizing the health of the population or dependent predators— (shown as Emsy in figure 2), which means overfishing occurred from 2010-2014 as the stock was collapsing. Federal scientists have proposed a way to better account for catches in Mexico and Canada that would help stabilize coastwide catches at target levels, but fishery managers have chosen to keep the current management regime in place.

Fishery managers did the right thing by closing the U.S. sardine fishery in 2015. However, they have not addressed the underlying management problems that allowed excessive fishing to occur during the collapse. Increasing the sardine cutoff and properly accounting for foreign catches could have lessened the crash, and these changes are necessary to rebuild the sardine population.

Our coastal fisheries and wildlife depend on it.

Figure 2. The West Coast Pacific sardine population (a.k.a. “northern subpopulation”) ranges from Baja California, Mexico to British Columbia, Canada. The total coastwide catch by the U.S., Mexico, and Canada exceeded maximum sustainable yield (catch) levels from 2010-2014. The U.S. alone exceeded maximum sustainable catch levels from 2012-2014. The maximum sustainable exploitation rate (Emsy)—the percentage of the fish biomass that can be removed—changes year to year depending on the temperature in the area off southern California where sardine spawn. Overfishing is defined as exceeding maximum sustainable yield.